Sunday, December 30, 2018

Monday, December 24, 2018

Merry Christmas Aunt Jeannie & Uncle Brain

on Christmas day to make you happy and cheerful

May Christmas spread cheer in your life

May this season of love warm your home

May this brighten your roads with hope

Merry Christmas to you and all your folks (Mika & Moto ).

Jonny , Sha , Jenny , Man Carano

Friday, December 21, 2018

Monday, December 17, 2018

fifteen year old climate activist tells UN climate sumit, " You are not mature enough to tell it like it is".

When Greta Thunberg, a 15-year-old climate activist from Sweden, had the chance to address a global climate change conference this past week, she told officials she had not come there to beg.

“You have ignored us in the past, and you will ignore us again,” she said.

“You say you love your children above all else, and yet you are stealing their future in front of their very eyes.”

Her remarks quickly gained attention on social media, and video of her speech was shared by leading climate scientists and elected officials. U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) tweeted footage of her address, saying she “called out world leaders for their global inaction on climate change.”

Sanders tweeted:

Sanders tweeted:

"Goosebumps! 15 year old activist @GretaThunberg speaks truth to power at the UN climate talks: "You say you love your children above all else, and yet you're stealing their future before their very eyes."

Thunberg accused leaders of speaking only about “green eternal economic growth because you are too scared of being unpopular.”

“You only talk about moving forward with the same bad ideas that got us into this mess even when the only sensible thing to do is pull the emergency brake,” she said. “You are not mature enough to tell it like it is.”

The 15-year-old spoke on behalf of Climate Justice Now, a global network of climate advocacy groups. Officials from nearly 200 countries gathered in Poland over the past two weeks to “nudge the world toward stronger targets for reducing carbon emissions and enshrine a clearer set of rules for how to get there,”

Thunberg might be young, but she’s already spent years working as a climate activist.

She first attracted media attention earlier this year when she went on strike from school, holding a sign outside the Swedish parliament building in Stockholm that read, “school strike for climate.” The New Yorker reported that Thunberg spent three weeks sitting in front of parliament during school hours, and later returned to classes for four days a week while continuing to protest on Fridays.

The jury for the Children’s Climate Prize wrote that she was nominated as a finalist this year because she has “shown more determination, dedication and strength in combating climate change and working for the future of humanity than most adults or politicians ever do.”

However, on Twitter, Greta asked to be removed from the list of finalists, noting that most people would have to fly to the awards ceremony. “All finalists are to be flown in from all over the world, to be a part of a ceremony, has no connection with reality,” she wrote. “Our generation will never be able to fly (among other things), other than for emergencies. Because the adult generations have used up all our carbon budget.”

Her family uses an electric car only when absolutely necessary. Otherwise, Greta uses her bicycle, the New Yorker wrote in a profile of her. Those are sacrifices she’s willing to make.

“Our biosphere is being sacrificed so that rich people in countries like mine can live in luxury,” she said this week. “It is the suffering of many that pay for the luxuries of few.”

GO GRETA!!!

GO GRETA!!!

Wednesday, December 12, 2018

Monday, December 10, 2018

Biggest mass extinction caused by global warming leaving ocean animals gasping for breath

December 6, 2018, University of Washington

The largest extinction in Earth's history marked the end of the Permian period, some 252 million years ago. Long before dinosaurs, our planet was populated with plants and animals that were mostly obliterated after a series of massive volcanic eruptions in Siberia.

Fossils in ancient seafloor rocks display a thriving and diverse marine ecosystem, then a swath of corpses. Some 96 percent of marine species were wiped out during the "Great Dying," followed by millions of years when life had to multiply and diversify once more.

What has been debated until now is exactly what made the oceans inhospitable to life—the high acidity of the water, metal and sulfide poisoning, a complete lack of oxygen, or simply higher temperatures.

New research from the University of Washington and Stanford University combines models of ocean conditions and animal metabolism with published lab data and paleoceanographic records to show that the Permian mass extinction in the oceans was caused by global warming that left animals unable to breathe. As temperatures rose and the metabolism of marine animals sped up, the warmer waters could not hold enough oxygen for them to survive.

The study is published in the Dec. 7 issue of Science.

"This is the first time that we have made a mechanistic prediction about what caused the extinction that can be directly tested with the fossil record, which then allows us to make predictions about the causes of extinction in the future," said first author Justin Penn, a UW doctoral student in oceanography.

Researchers ran a climate model with Earth's configuration during the Permian, when the land masses were combined in the supercontinent of Pangaea. Before ongoing volcanic eruptions in Siberia created a greenhouse-gas planet, oceans had temperatures and oxygen levels similar to today's. The researchers then raised greenhouse gases in the model to the level required to make tropical ocean temperatures at the surface some 10 degrees Celsius (20 degrees Fahrenheit) higher, matching conditions at that time.

The model reproduces the resulting dramatic changes in the oceans. Oceans lost about 80 percent of their oxygen. About half the oceans' seafloor, mostly at deeper depths, became completely oxygen-free.

To analyze the effects on marine species, the researchers considered the varying oxygen and temperature sensitivities of 61 modern marine species—including crustaceans, fish, shellfish, corals and sharks—using published lab measurements. The tolerance of modern animals to high temperature and low oxygen is expected to be similar to Permian animals because they had evolved under similar environmental conditions. The researchers then combined the species' traits with the paleoclimate simulations to predict the geography of the extinction.

"Very few marine organisms stayed in the same habitats they were living in—it was either flee or perish," said second author Curtis Deutsch, a UW associate professor of oceanography.

This roughly 1.5-foot slab of rock from southern China shows the Permian-Triassic boundary. The bottom section is pre-extinction limestone. The upper section is microbial limestone deposited after the extinction. Credit: Jonathan Payne/Stanford University

The model shows the hardest hit were organisms most sensitive to oxygen found far from the tropics. Many species that lived in the tropics also went extinct in the model, but it predicts that high-latitude species, especially those with high oxygen demands, were nearly completely wiped out.

To test this prediction, co-authors Jonathan Payne and Erik Sperling at Stanford analyzed late-Permian fossil distributions from the Paleoceanography Database, a virtual archive of published fossil collections. The fossil record shows where species were before the extinction, and which were wiped out completely or restricted to a fraction of their former habitat.

The fossil record confirms that species far from the equator suffered most during the event.

"The signature of that kill mechanism, climate warming and oxygen loss, is this geographic pattern that's predicted by the model and then discovered in the fossils," Penn said. "The agreement between the two indicates this mechanism of climate warming and oxygen loss was a primary cause of the extinction."

The study builds on previous work led by Deutsch showing that as oceans warm, marine animals' metabolism speeds up, meaning they require more oxygen, while warmer water holds less. That earlier study shows how warmer oceans push animals away from the tropics.

The new study combines the changing ocean conditions with various animals' metabolic needs at different temperatures. Results show that the most severe effects of oxygen deprivation are for species living near the poles.

"Since tropical organisms' metabolisms were already adapted to fairly warm, lower-oxygen conditions, they could move away from the tropics and find the same conditions somewhere else," Deutsch said. "But if an organism was adapted for a cold, oxygen-rich environment, then those conditions ceased to exist in the shallow oceans."

The so-called "dead zones" that are completely devoid of oxygen were mostly below depths where species were living, and played a smaller role in the survival rates."At the end of the day, it turned out that the size of the dead zones really doesn't seem to be the key thing for the extinction," Deutsch said. "We often think about anoxia, the complete lack of oxygen, as the condition you need to get widespread uninhabitability. But when you look at the tolerance for low oxygen, most organisms can be excluded from seawater at oxygen levels that aren't anywhere close to anoxic."

Warming leading to insufficient oxygen explains more than half of the marine diversity losses. The authors say that other changes, such as acidification or shifts in the productivity of photosynthetic organisms, likely acted as additional causes.

The situation in the late Permian—increasing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere that create warmer temperatures on Earth—is similar to today.

"Under a business-as-usual emissions scenarios, by 2100 warming in the upper ocean will have approached 20 percent of warming in the late Permian, and by the year 2300 it will reach between 35 and 50 percent," Penn said. "This study highlights the potential for a mass extinction arising from a similar mechanism under anthropogenic climate change."

Thanx University of Washington

Knight Man

The largest extinction in Earth's history marked the end of the Permian period, some 252 million years ago. Long before dinosaurs, our planet was populated with plants and animals that were mostly obliterated after a series of massive volcanic eruptions in Siberia.

Fossils in ancient seafloor rocks display a thriving and diverse marine ecosystem, then a swath of corpses. Some 96 percent of marine species were wiped out during the "Great Dying," followed by millions of years when life had to multiply and diversify once more.

What has been debated until now is exactly what made the oceans inhospitable to life—the high acidity of the water, metal and sulfide poisoning, a complete lack of oxygen, or simply higher temperatures.

New research from the University of Washington and Stanford University combines models of ocean conditions and animal metabolism with published lab data and paleoceanographic records to show that the Permian mass extinction in the oceans was caused by global warming that left animals unable to breathe. As temperatures rose and the metabolism of marine animals sped up, the warmer waters could not hold enough oxygen for them to survive.

The study is published in the Dec. 7 issue of Science.

"This is the first time that we have made a mechanistic prediction about what caused the extinction that can be directly tested with the fossil record, which then allows us to make predictions about the causes of extinction in the future," said first author Justin Penn, a UW doctoral student in oceanography.

Researchers ran a climate model with Earth's configuration during the Permian, when the land masses were combined in the supercontinent of Pangaea. Before ongoing volcanic eruptions in Siberia created a greenhouse-gas planet, oceans had temperatures and oxygen levels similar to today's. The researchers then raised greenhouse gases in the model to the level required to make tropical ocean temperatures at the surface some 10 degrees Celsius (20 degrees Fahrenheit) higher, matching conditions at that time.

The model reproduces the resulting dramatic changes in the oceans. Oceans lost about 80 percent of their oxygen. About half the oceans' seafloor, mostly at deeper depths, became completely oxygen-free.

To analyze the effects on marine species, the researchers considered the varying oxygen and temperature sensitivities of 61 modern marine species—including crustaceans, fish, shellfish, corals and sharks—using published lab measurements. The tolerance of modern animals to high temperature and low oxygen is expected to be similar to Permian animals because they had evolved under similar environmental conditions. The researchers then combined the species' traits with the paleoclimate simulations to predict the geography of the extinction.

"Very few marine organisms stayed in the same habitats they were living in—it was either flee or perish," said second author Curtis Deutsch, a UW associate professor of oceanography.

This roughly 1.5-foot slab of rock from southern China shows the Permian-Triassic boundary. The bottom section is pre-extinction limestone. The upper section is microbial limestone deposited after the extinction. Credit: Jonathan Payne/Stanford University

The model shows the hardest hit were organisms most sensitive to oxygen found far from the tropics. Many species that lived in the tropics also went extinct in the model, but it predicts that high-latitude species, especially those with high oxygen demands, were nearly completely wiped out.

To test this prediction, co-authors Jonathan Payne and Erik Sperling at Stanford analyzed late-Permian fossil distributions from the Paleoceanography Database, a virtual archive of published fossil collections. The fossil record shows where species were before the extinction, and which were wiped out completely or restricted to a fraction of their former habitat.

The fossil record confirms that species far from the equator suffered most during the event.

"The signature of that kill mechanism, climate warming and oxygen loss, is this geographic pattern that's predicted by the model and then discovered in the fossils," Penn said. "The agreement between the two indicates this mechanism of climate warming and oxygen loss was a primary cause of the extinction."

The study builds on previous work led by Deutsch showing that as oceans warm, marine animals' metabolism speeds up, meaning they require more oxygen, while warmer water holds less. That earlier study shows how warmer oceans push animals away from the tropics.

The new study combines the changing ocean conditions with various animals' metabolic needs at different temperatures. Results show that the most severe effects of oxygen deprivation are for species living near the poles.

"Since tropical organisms' metabolisms were already adapted to fairly warm, lower-oxygen conditions, they could move away from the tropics and find the same conditions somewhere else," Deutsch said. "But if an organism was adapted for a cold, oxygen-rich environment, then those conditions ceased to exist in the shallow oceans."

The so-called "dead zones" that are completely devoid of oxygen were mostly below depths where species were living, and played a smaller role in the survival rates."At the end of the day, it turned out that the size of the dead zones really doesn't seem to be the key thing for the extinction," Deutsch said. "We often think about anoxia, the complete lack of oxygen, as the condition you need to get widespread uninhabitability. But when you look at the tolerance for low oxygen, most organisms can be excluded from seawater at oxygen levels that aren't anywhere close to anoxic."

Warming leading to insufficient oxygen explains more than half of the marine diversity losses. The authors say that other changes, such as acidification or shifts in the productivity of photosynthetic organisms, likely acted as additional causes.

The situation in the late Permian—increasing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere that create warmer temperatures on Earth—is similar to today.

"Under a business-as-usual emissions scenarios, by 2100 warming in the upper ocean will have approached 20 percent of warming in the late Permian, and by the year 2300 it will reach between 35 and 50 percent," Penn said. "This study highlights the potential for a mass extinction arising from a similar mechanism under anthropogenic climate change."

Thanx University of Washington

Knight Man

Sunday, December 9, 2018

Friday, December 7, 2018

On Climate, the Facts and Law Are Against Trump

By Richard L. Revesz Dec. 4, 2018

Mr. Revesz is a professor at the New York University School of Law.

A Trump rally in West Virginia on Aug. 21, the day the government announced plans to weaken regulations on coal plants.CreditCreditMandel Ngan/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

A major governmental report released by the Trump administration recently projects enormous damages to communities across the country as a result of climate change. This new volume of the congressionally mandated National Climate Assessment includes more alarming predictions than its predecessors did, and it officially puts the Trump administration on the record about the dire threats Americans face.

The report is likely to bolster anticipated lawsuits against the administration over its decision to vastly weaken the nation’s two major climate change regulations, which would limit planet-warming emissions from power plants and vehicles, the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions. The new report could play a key role in these lawsuits.

The administration lawyers who end up arguing these cases may find themselves turning to Carl Sandburg’s famous advice: “If the facts are against you, argue the law. If the law is against you, argue the facts. If the law and the facts are against you, pound the table and yell like hell.”

Now that this report is part of the official government record, the administration cannot credibly suggest that climate policies should be weakened. Prepared by dozens of experts and government officials, the assessment predicts hundreds of billions of dollars in damages from storms, crop failures, ruined infrastructure and climate-related deaths and illnesses. Stronger regulations to limit emissions are needed, it says.

With the facts against it, the administration will have to argue the law. But that approach has already led to numerous lost deregulatory cases. At the Institute for Policy Integrity, which I direct at the New York University School of Law, we have kept a tally of court challenges to Trump-era deregulatory rules. The administration’s record is dismal: It prevailed in two cases and either lost or abandoned its position in 20 others.

I don't understand Trump at all. Climate scientists are predicting dire circumstances if we don't restrict the burning of fossils fuels. Trump on the other hand advocates the burning of fossil fuels in order to keep some jobs. So we keep some jobs for now and 30,50 100 years from now the land mass of the united states is considerably reduced by the rising oceans, not to mention the incredible loss of life. I don't think Trump is stupid, he knows what he is doing. I think Trump is evil.

So not only have the facts been against the government’s position. So has the law.

On the power plant emissions rule, the administration’s own analysis shows that its weaker regulatory scheme will be dramatically worse for the public. In fact, the administration’s so-called Affordable Clean Energy Rule is likely to increase overall emissions by creating new loopholes for coal plants to evade air pollution restrictions and operate more frequently. That will cause a significant increase in climate pollution and up to 1,400 additional American deaths per year, according to the government’s projections. The E.P.A. says that it is exercising its discretion in choosing this rule, which will impose tens of billions of dollars of net harms on the American people. This is a textbook example of “arbitrary and capricious” conduct — exactly what the law prohibits.

In weakening the vehicle emissions rule, the administration relies on economic and legal arguments that don’t stand up to scrutiny. The current standards require automakers to steadily increase the fuel efficiency of new passenger vehicles, limiting climate pollution while reducing consumer fuel costs.

The Trump administration has proposed freezing the standards in 2021 and revoking a waiver that allows California to set its own, more stringent vehicle pollution limits, which other states follow.

Officials claim the resulting increases in pollution and fuel costs are justified by supposed safety benefits from rolling back the standards. It assumes that stricter efficiency standards raise the price of vehicles. Standard economic theory predicts that people would then buy fewer cars because each car would be more expensive. But instead, the administration’s faulty analysis leads it, wholly implausibly, to the opposite conclusion: that people will buy more cars, and therefore drive more miles and have more accidents.

Even Andrew Wheeler, the acting E.P.A. administrator whom Trump has nominated for the post, reportedly argued that this justification will fail in court. Yet the administration released the proposal anyway. At the same time, despite a lack of legal authority to do so, the administration has proposed to revoke California’s waiver, a move without precedent. Doing so would trample on the interests of California and other states that have relied on the waiver to set policies for their benefit, and do violence to core principles of federalism. Again, on these issues, the law is against the administration.

So without the facts or law on its side, the Trump administration may have no choice but to “pound the table and yell like hell” when explaining its willful inaction on climate change. It may yell about “freedom” — a rhetorical cover frequently used by administration officials trying to justify efforts to let industry pollute freely, regardless of public health consequences. For instance, Neomi Rao, the regulatory czar nominated to fill Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s federal court seat, wrote recently that the administration’s deregulatory efforts are about “unleashing the freedom of American workers, innovators and businesses.”

The freedom that the Trump administration favors has little to do with what the founding fathers prized. It is a freedom for favored industries to impose numerous premature deaths, hospitalizations and other major harms on the public in pursuit of profit, even when the net cost to society is large.

The Trump administration will have nothing to show for pounding its fists and yelling. Without the facts or the law on its side, these antics won’t be an adequate legal defense for the administration’s choice to undermine the very climate policies its report says are needed to protect Americans.

Richard L. Revesz is a professor and dean emeritus at the New York University School of Law, where he directs the Institute for Policy Integrity.

Thanx Richard L. Revesz

Knight Jonny

Mr. Revesz is a professor at the New York University School of Law.

A Trump rally in West Virginia on Aug. 21, the day the government announced plans to weaken regulations on coal plants.CreditCreditMandel Ngan/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

A major governmental report released by the Trump administration recently projects enormous damages to communities across the country as a result of climate change. This new volume of the congressionally mandated National Climate Assessment includes more alarming predictions than its predecessors did, and it officially puts the Trump administration on the record about the dire threats Americans face.

The report is likely to bolster anticipated lawsuits against the administration over its decision to vastly weaken the nation’s two major climate change regulations, which would limit planet-warming emissions from power plants and vehicles, the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions. The new report could play a key role in these lawsuits.

The administration lawyers who end up arguing these cases may find themselves turning to Carl Sandburg’s famous advice: “If the facts are against you, argue the law. If the law is against you, argue the facts. If the law and the facts are against you, pound the table and yell like hell.”

Now that this report is part of the official government record, the administration cannot credibly suggest that climate policies should be weakened. Prepared by dozens of experts and government officials, the assessment predicts hundreds of billions of dollars in damages from storms, crop failures, ruined infrastructure and climate-related deaths and illnesses. Stronger regulations to limit emissions are needed, it says.

With the facts against it, the administration will have to argue the law. But that approach has already led to numerous lost deregulatory cases. At the Institute for Policy Integrity, which I direct at the New York University School of Law, we have kept a tally of court challenges to Trump-era deregulatory rules. The administration’s record is dismal: It prevailed in two cases and either lost or abandoned its position in 20 others.

I don't understand Trump at all. Climate scientists are predicting dire circumstances if we don't restrict the burning of fossils fuels. Trump on the other hand advocates the burning of fossil fuels in order to keep some jobs. So we keep some jobs for now and 30,50 100 years from now the land mass of the united states is considerably reduced by the rising oceans, not to mention the incredible loss of life. I don't think Trump is stupid, he knows what he is doing. I think Trump is evil.

So not only have the facts been against the government’s position. So has the law.

On the power plant emissions rule, the administration’s own analysis shows that its weaker regulatory scheme will be dramatically worse for the public. In fact, the administration’s so-called Affordable Clean Energy Rule is likely to increase overall emissions by creating new loopholes for coal plants to evade air pollution restrictions and operate more frequently. That will cause a significant increase in climate pollution and up to 1,400 additional American deaths per year, according to the government’s projections. The E.P.A. says that it is exercising its discretion in choosing this rule, which will impose tens of billions of dollars of net harms on the American people. This is a textbook example of “arbitrary and capricious” conduct — exactly what the law prohibits.

In weakening the vehicle emissions rule, the administration relies on economic and legal arguments that don’t stand up to scrutiny. The current standards require automakers to steadily increase the fuel efficiency of new passenger vehicles, limiting climate pollution while reducing consumer fuel costs.

The Trump administration has proposed freezing the standards in 2021 and revoking a waiver that allows California to set its own, more stringent vehicle pollution limits, which other states follow.

Officials claim the resulting increases in pollution and fuel costs are justified by supposed safety benefits from rolling back the standards. It assumes that stricter efficiency standards raise the price of vehicles. Standard economic theory predicts that people would then buy fewer cars because each car would be more expensive. But instead, the administration’s faulty analysis leads it, wholly implausibly, to the opposite conclusion: that people will buy more cars, and therefore drive more miles and have more accidents.

Even Andrew Wheeler, the acting E.P.A. administrator whom Trump has nominated for the post, reportedly argued that this justification will fail in court. Yet the administration released the proposal anyway. At the same time, despite a lack of legal authority to do so, the administration has proposed to revoke California’s waiver, a move without precedent. Doing so would trample on the interests of California and other states that have relied on the waiver to set policies for their benefit, and do violence to core principles of federalism. Again, on these issues, the law is against the administration.

So without the facts or law on its side, the Trump administration may have no choice but to “pound the table and yell like hell” when explaining its willful inaction on climate change. It may yell about “freedom” — a rhetorical cover frequently used by administration officials trying to justify efforts to let industry pollute freely, regardless of public health consequences. For instance, Neomi Rao, the regulatory czar nominated to fill Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s federal court seat, wrote recently that the administration’s deregulatory efforts are about “unleashing the freedom of American workers, innovators and businesses.”

The freedom that the Trump administration favors has little to do with what the founding fathers prized. It is a freedom for favored industries to impose numerous premature deaths, hospitalizations and other major harms on the public in pursuit of profit, even when the net cost to society is large.

The Trump administration will have nothing to show for pounding its fists and yelling. Without the facts or the law on its side, these antics won’t be an adequate legal defense for the administration’s choice to undermine the very climate policies its report says are needed to protect Americans.

Richard L. Revesz is a professor and dean emeritus at the New York University School of Law, where he directs the Institute for Policy Integrity.

Thanx Richard L. Revesz

Knight Jonny

Thursday, December 6, 2018

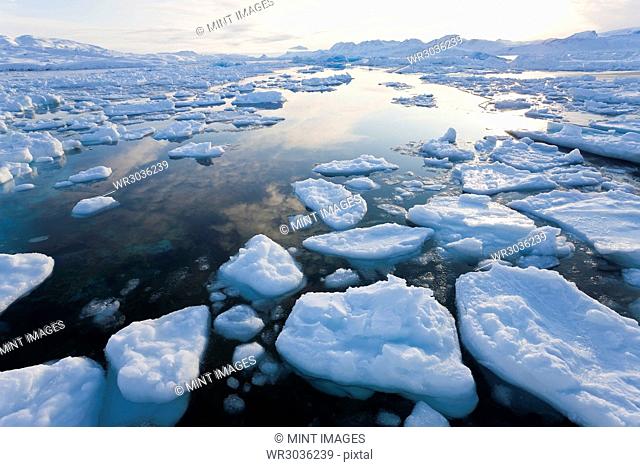

Greenland is melting ..... What unprecedented' ice loss means for Earth

The ice sheet is melting faster than in the last 350 years—and driving sea levels up around the world.

For a few days in July of 2012, it was so hot in the Arctic that nearly the entire surface of the Greenland ice sheet turned to slush.

It was so uncharacteristically warm that scientists, emerging from their tents high on the peak of the ice sheet, sank up to their knees in the suddenly soft snow. And then, that snow started melting.

Near the edge of the ice sheet, bright blue puddles collected on the flat white surface. Rivulets of melt trickled down, braiding into fat, gushing rivers. The meltwater punched through gullies and spilled down crevasses. One river near the edge of the ice sheet was so swollen that it swept away a bridge that had been there for decades. So much water spilled out of the guts of the ice sheet that year that global sea levels rose by over a millimeter.

The melting was alarming, like nothing scientists had seen before. But no one knew exactly how unusual the event was or how worried to be. But now, scientists have figured out that the hot 2012 summer capped off 20 years of unprecedented increases in meltwater runoff from Greenland. And even more concerning, they found, melting is speeding up even faster than air temperatures warm. So yes, they found, 2012 was a particularly bad year—but it was just a preview of what might come.

“The melting of the Greenland ice sheet is greater than at any point in the last three to four centuries, and probably much longer than that,” says Luke Trusel, a researcher at Rowan University in New Jersey and lead author of the new study, published today in Nature

And the effects of the melting aren’t just abstract: A complete melting of Greenland’s mile-thick ice sheets would dump seven meters (23 feet) of extra water into the world’s ocean. So what happens high in the poles matters to anyone who lives near a coast, eats food that comes through a coastal port, or makes a flight connection in an airport near the ocean, scientists warn.

Reading the ice like a book of the past

Scientists already knew that Greenland was melting fast; they could track its shrinking size from satellites. But the key satellite data only goes back until the early 1990s—so they couldn’t tell exactly how alarmed to be by the melting. Had this kind of jaw-dropping warming happened before? How unusual was it, compared to the time before human-caused climate change kicked into gear? No one knew.

They had to figure out a way to look back in time, so they went to the source: the ice sheet itself. They fanned across the ice surface and drilled a suite of ice cores that recorded signals of how much and how intensely the surface of the ice sheet had melted over the past few hundred years. They compared that with models, which let them calculate how much runoff would result from the kind of surface melting recorded in the ice cores.

And in both, they saw a clear signal. Melting and runoff started creeping upward just when the first stirrings of human-caused climate change hit the Arctic, in the mid-19th century. But the real drama unfolded in the past 20 years; suddenly, melt intensity shot up, up to nearly six-fold higher than it was before the Industrial Revolution.

“It’s really like turning on a switch,” says Beata Csatho, a glaciologist at the University at Buffalo.

And in both, they saw a clear signal. Melting and runoff started creeping upward just when the first stirrings of human-caused climate change hit the Arctic, in the mid-19th century. But the real drama unfolded in the past 20 years; suddenly, melt intensity shot up, up to nearly six-fold higher than it was before the Industrial Revolution.

“It’s really like turning on a switch,” says Beata Csatho, a glaciologist at the University at Buffalo.

The blob effect

It was also clear that melting was speeding up faster than the temperature rose. The warmer it got, the more sensitive the ice sheet was to that warming, primarily because melting at the surface changes its color.

“Think of a white fluffy snowflake,” explains Trusel. “As it melts, it’s going to become a blob.”

And blobs absorb more of the sun’s heat than fluffy, bright-white flakes. And the more heat they absorb, the blobbier they become, and the more they melt. “So even without any temperature change, once they get set in motion they just want to melt even more,” says Trusel.

That doesn’t bode well for the future, particularly because air temperatures in the Arctic are rising faster than anywhere else on the planet.

“What we're seeing right now is really unprecedented. These melt increases are driven by warming, which is caused by humans pumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere,” says Ellyn Enderlin, a glacier scientist at the University of Maine. “The feedbacks the Earth has, the checks it has—they can't make up for that. The system can't adjust to the rate of change right now.”

Sunday, December 2, 2018

Moto the Wanna-be Knight

My sweet little Mika on the right and funny old Moto on the left

always looks like he has a headache

Moto on a very bad hair day

This time it looks like he has a pain in his right eye

In this photo he seems a wee bit constipated

We will photograph him in his armor and see if we can make him look good.

He's so happy you are going to Knight him and would like to know if he has to write a post to become a knight... or just memorize the Knights' Oath.

He once considered becoming an artist

but he got a headache and took a nap

Friday, November 30, 2018

Why Does California Have So Many Wildfires?

A house set alight by the Camp Fire in Paradise, Calif., on Thursday. The fast-spreading fire has been burning 80 acres per minute.CreditCreditNoah Berger/Associated Press

By Kendra Pierre-Louis Nov. 9, 2018

A pregnant woman went into labor while being evacuated. Videos showed dozens of harrowing drives through fiery landscapes. Pleas appeared on social media seeking the whereabouts of loved ones. Survivors of a mass shooting were forced to flee approaching flames.

This has been California since the Camp Fire broke out early Thursday morning, burning 80 acres per minute and devastating the northern town of Paradise. Later in the day, the Woolsey Fire broke out to the south in Ventura and Los Angeles Counties, prompting the evacuation of all of Malibu.

What is it about California that makes wildfires so catastrophic? There are four key ingredients.

The (changing) climate

The first is California’s climate.

“Fire, in some ways, is a very simple thing,” said Park Williams, a bioclimatologist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. “As long as stuff is dry enough and there’s a spark, then that stuff will burn.”

California, like much of the West, gets most of its moisture in the fall and winter. Its vegetation then spends much of the summer slowly drying out because of a lack of rainfall and warmer temperatures. That vegetation then serves as kindling for fires.

But while California’s climate has always been fire prone, the link between climate change and bigger fires is inextricable. “Behind the scenes of all of this, you’ve got temperatures that are about two to three degrees Fahrenheit warmer now than they would’ve been without global warming,” Dr. Williams said. That dries out vegetation even more, making it more likely to burn.

California’s fire record dates back to 1932; of the 10 largest fires since then, nine have occurred since 2000, five since 2010 and two this year alone, including the Mendocino Complex Fire, the largest in state history.

“In pretty much every single way, a perfect recipe for fire is just kind of written in California,” Dr. Williams said. “Nature creates the perfect conditions for fire, as long as people are there to start the fires. But then climate change, in a few different ways, seems to also load the dice toward more fire in the future.”

California Fires Map ; Tracking the spread

Wildfires have burned in California near the Sierra Nevada foothills and the Los Angeles shoreline , engulfing nearly 250,000 acres November 11 , 2018 .

People

Even if the conditions are right for a wildfire, you still need something or someone to ignite it. Sometimes the trigger is nature, like a lightning strike, but more often than not humans are responsible.

“Many of these large fires that you’re seeing in Southern California and impacting the areas where people are living are human-caused,” said Nina S. Oakley, an assistant research professor of atmospheric science at the Desert Research Institute.

Deadly fires in and around Sonoma County last year were started by downed power lines. This year’s Carr Fire, the state’s sixth-largest on record, started when a truck blew out its tire and its rim scraped the pavement, sending out sparks.

“California has a lot of people and a really long dry season,” Dr. Williams said. “People are always creating possible sparks, and as the dry season wears on and stuff is drying out more and more, the chance that a spark comes off a person at the wrong time just goes up. And that’s putting aside arson.”

There’s another way people have contributed to wildfires: in their choices of where to live. People are increasingly moving into areas near forests, known as the urban-wildland interface, that are inclined to burn.

“In Nevada, we have many, many large fires, but typically they’re burning open spaces,” Dr. Oakley said. “They’re not burning through neighborhoods.”

What on Earth Is Going On?

Patients were evacuated from the Feather River Hospital in Paradise, Calif.Credit Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Fire suppression

It’s counterintuitive, but the United States’ history of suppressing wildfires has actually made present-day wildfires worse.

“For the last century we fought fire, and we did pretty well at it across all of the Western United States,” Dr. Williams said. “And every time we fought a fire successfully, that means that a bunch of stuff that would have burned didn’t burn. And so over the last hundred years we’ve had an accumulation of plants in a lot of areas.

“And so in a lot of California now when fires start, those fires are burning through places that have a lot more plants to burn than they would have if we had been allowing fires to burn for the last hundred years.”

In recent years, the United States Forest Service has been trying to rectify the previous practice through the use of prescribed or “controlled” burns.

The Santa Ana winds

Each fall, strong gusts known as the Santa Ana winds bring dry air from the Great Basin area of the West into Southern California, said Fengpeng Sun, an assistant professor in the department of geosciences at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Dr. Sun is a co-author of a 2015 study that suggests that California has two distinct fire seasons. One, which runs from June through September and is driven by a combination of warmer and drier weather, is the Western fire season that most people think of. Those wildfires tend to be more inland, in higher-elevation forests.

But Dr. Sun and his co-authors also identified a second fire season that runs from October through April and is driven by the Santa Ana winds. Those fires tend to spread three times faster and burn closer to urban areas, and they were responsible for 80 percent of the economic losses over two decades beginning in 1990.

[Minorities are most vulnerable when wildfires strike in the United States, a study found.]

It’s not just that the Santa Ana winds dry out vegetation; they also move embers around, spreading fires.

If the fall rains, which usually begin in October, fail to arrive on time, as they did this year, the winds can make already dry conditions even drier. During an average October, Northern California can get more than two inches of rain, according to Derek Arndt, chief of the monitoring branch at the National Centers for Environmental Information, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. This year, in some places, less than half that amount fell.

“None of these are like, record-breaking, historically dry for October,” Dr. Arndt said. “But they’re all on the dry side of history.”

Kendra Pierre-Louis is a reporter on the climate team. Before joining The Times in 2017, she covered science and the environment for Popular Science. @kendrawrites

Thanx Kendra Pierre-Louis

Knight Jonny

By Kendra Pierre-Louis Nov. 9, 2018

A pregnant woman went into labor while being evacuated. Videos showed dozens of harrowing drives through fiery landscapes. Pleas appeared on social media seeking the whereabouts of loved ones. Survivors of a mass shooting were forced to flee approaching flames.

This has been California since the Camp Fire broke out early Thursday morning, burning 80 acres per minute and devastating the northern town of Paradise. Later in the day, the Woolsey Fire broke out to the south in Ventura and Los Angeles Counties, prompting the evacuation of all of Malibu.

What is it about California that makes wildfires so catastrophic? There are four key ingredients.

The (changing) climate

The first is California’s climate.

“Fire, in some ways, is a very simple thing,” said Park Williams, a bioclimatologist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. “As long as stuff is dry enough and there’s a spark, then that stuff will burn.”

California, like much of the West, gets most of its moisture in the fall and winter. Its vegetation then spends much of the summer slowly drying out because of a lack of rainfall and warmer temperatures. That vegetation then serves as kindling for fires.

But while California’s climate has always been fire prone, the link between climate change and bigger fires is inextricable. “Behind the scenes of all of this, you’ve got temperatures that are about two to three degrees Fahrenheit warmer now than they would’ve been without global warming,” Dr. Williams said. That dries out vegetation even more, making it more likely to burn.

California’s fire record dates back to 1932; of the 10 largest fires since then, nine have occurred since 2000, five since 2010 and two this year alone, including the Mendocino Complex Fire, the largest in state history.

“In pretty much every single way, a perfect recipe for fire is just kind of written in California,” Dr. Williams said. “Nature creates the perfect conditions for fire, as long as people are there to start the fires. But then climate change, in a few different ways, seems to also load the dice toward more fire in the future.”

California Fires Map ; Tracking the spread

Wildfires have burned in California near the Sierra Nevada foothills and the Los Angeles shoreline , engulfing nearly 250,000 acres November 11 , 2018 .

People

Even if the conditions are right for a wildfire, you still need something or someone to ignite it. Sometimes the trigger is nature, like a lightning strike, but more often than not humans are responsible.

“Many of these large fires that you’re seeing in Southern California and impacting the areas where people are living are human-caused,” said Nina S. Oakley, an assistant research professor of atmospheric science at the Desert Research Institute.

Deadly fires in and around Sonoma County last year were started by downed power lines. This year’s Carr Fire, the state’s sixth-largest on record, started when a truck blew out its tire and its rim scraped the pavement, sending out sparks.

“California has a lot of people and a really long dry season,” Dr. Williams said. “People are always creating possible sparks, and as the dry season wears on and stuff is drying out more and more, the chance that a spark comes off a person at the wrong time just goes up. And that’s putting aside arson.”

There’s another way people have contributed to wildfires: in their choices of where to live. People are increasingly moving into areas near forests, known as the urban-wildland interface, that are inclined to burn.

“In Nevada, we have many, many large fires, but typically they’re burning open spaces,” Dr. Oakley said. “They’re not burning through neighborhoods.”

What on Earth Is Going On?

Patients were evacuated from the Feather River Hospital in Paradise, Calif.Credit Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Fire suppression

It’s counterintuitive, but the United States’ history of suppressing wildfires has actually made present-day wildfires worse.

“For the last century we fought fire, and we did pretty well at it across all of the Western United States,” Dr. Williams said. “And every time we fought a fire successfully, that means that a bunch of stuff that would have burned didn’t burn. And so over the last hundred years we’ve had an accumulation of plants in a lot of areas.

“And so in a lot of California now when fires start, those fires are burning through places that have a lot more plants to burn than they would have if we had been allowing fires to burn for the last hundred years.”

In recent years, the United States Forest Service has been trying to rectify the previous practice through the use of prescribed or “controlled” burns.

The Santa Ana winds

Each fall, strong gusts known as the Santa Ana winds bring dry air from the Great Basin area of the West into Southern California, said Fengpeng Sun, an assistant professor in the department of geosciences at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Dr. Sun is a co-author of a 2015 study that suggests that California has two distinct fire seasons. One, which runs from June through September and is driven by a combination of warmer and drier weather, is the Western fire season that most people think of. Those wildfires tend to be more inland, in higher-elevation forests.

But Dr. Sun and his co-authors also identified a second fire season that runs from October through April and is driven by the Santa Ana winds. Those fires tend to spread three times faster and burn closer to urban areas, and they were responsible for 80 percent of the economic losses over two decades beginning in 1990.

[Minorities are most vulnerable when wildfires strike in the United States, a study found.]

It’s not just that the Santa Ana winds dry out vegetation; they also move embers around, spreading fires.

If the fall rains, which usually begin in October, fail to arrive on time, as they did this year, the winds can make already dry conditions even drier. During an average October, Northern California can get more than two inches of rain, according to Derek Arndt, chief of the monitoring branch at the National Centers for Environmental Information, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. This year, in some places, less than half that amount fell.

“None of these are like, record-breaking, historically dry for October,” Dr. Arndt said. “But they’re all on the dry side of history.”

Kendra Pierre-Louis is a reporter on the climate team. Before joining The Times in 2017, she covered science and the environment for Popular Science. @kendrawrites

Thanx Kendra Pierre-Louis

Knight Jonny

Wednesday, November 28, 2018

Dead whale found with 13 pounds of plastic in stomach

Nov. 21, 2018 - A dead sperm whale washed ashore in eastern Indonesia with 13 pounds of plastic in its stomach. The trash included 115 drinking cups, 25 plastic bags, plastic bottles, two flip-flops, and more than 1,000 pieces of string. The whale’s exact cause of death is unknown, but observers say the whale may highlight the global plastic pollution problem.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

The findings from the two expeditions, found that the patch covers 1.6 million square kilometers (617,000 sq. miles) with a concentration of 10–100 kg per square kilometer. They estimate an 80,000 metric tons in the patch, with 1.8 trillion plastic pieces, out of which 92% of the mass is to be found in objects larger than 0.5 centimeters.

IT'S TWICE THE SIZE OF TEXAS

Closeup below

Moto - The Wanna-be Knight

Jake and Moto

Moto is Mika's brother. He's jealous because he wants to be a knight too. The problem is Moto is not cute at all and Mika doesn't like him much.

Monday, November 26, 2018

Sunday, November 25, 2018

When Will We Accept That Climate Change Is Real? /sites/enriquedans/

Enrique Dans Contributor November 18 , 2018

Leadership Strategy Teaching and consulting in the innovation field since 1990

A street sign sits submerged in floodwater after Hurricane Florence hit in Bergaw, North Carolina, U.S., on Friday, Sept. 21, 2018. President Donald Trump lauded the federal response to Hurricane Florence on Wednesday as he began a tour of areas in North and South Carolina hit over the weekend by high winds and torrential rain. Photographer: Callaghan O'Hare/Bloomberg© 2018 Bloomberg Finance LP

The US National Climate Assessment (NCA) has just published a report on the impact, risks and adaptation of the United States to climate change, and concludes, radically contradicting the opinion of the country’s irresponsible president, that the impact is already being felt and will be devastating in the near future, involving from tens of thousands of deaths to hundreds of billions of dollars in damages. And the Trump administration’s reaction to the report? To publish it on Black Friday, the biggest shopping day of the year, hoping it will go unnoticed. While the report highlights the growing cost of doing nothing, Donald Trump insists on doing exactly that: nothing.

We can expect more reports of this type as scientists join the dots of the global phenomenon we are experiencing: the stronger hurricanes, heat waves, fires and floods ravaging the planet are not a coincidence or bad luck, but are instead the result of a climate catastrophe. The mountain ranges in the west of the country retain less snow throughout the year and threaten the water supply of their basins. Coral reefs in the Caribbean, Hawaii, Florida and the Pacific territories are being bleached, seriously threatening the ecosystems they shelter.

Fires devour increasingly larger areas in seasons that are getting longer and longer. Alaska, the only arctic state in the country, is undergoing rapid warming that is drastically changing its ecosystem, melting its coastlines and its permafrost tundra. And the Carolinas are still underwater from flooding brought on by Hurricane Florence.

The 1,600-page report is the result of the collaboration of 13 federal agencies: more than a thousand people, including three hundred leading scientists in the field. It is not a report to take lightly or to dismiss as alarmist, unless you are irresponsible, an imbecile, or both.

The magnitude of the problem requires a broad consensus to launch immediate action. Immediate means now, not in 2040. With the right measures we can still produce tangible effects that will improve the situation: as we let time go by, this will be nigh impossible to achieve and the cost beyond calculation. Failing to take immediate action will mean greater impact that will be harder to counter.

We have to grasp this and stop making excuses: we’re no longer talking problems for our grandchildren, but effects we are all going to witness within our lifespan. Meanwhile, irresponsible sections of society prefer to look the other way, dismiss the experts, drag their feet, come up with unsustainable arguments or just plain lies: but the simple truth is that the catastrophe is already unfolding around us.

Thanx Enrique Dans

Crusader Jenny , Nanook & Knight Mika

Leadership Strategy Teaching and consulting in the innovation field since 1990

A street sign sits submerged in floodwater after Hurricane Florence hit in Bergaw, North Carolina, U.S., on Friday, Sept. 21, 2018. President Donald Trump lauded the federal response to Hurricane Florence on Wednesday as he began a tour of areas in North and South Carolina hit over the weekend by high winds and torrential rain. Photographer: Callaghan O'Hare/Bloomberg© 2018 Bloomberg Finance LP

The US National Climate Assessment (NCA) has just published a report on the impact, risks and adaptation of the United States to climate change, and concludes, radically contradicting the opinion of the country’s irresponsible president, that the impact is already being felt and will be devastating in the near future, involving from tens of thousands of deaths to hundreds of billions of dollars in damages. And the Trump administration’s reaction to the report? To publish it on Black Friday, the biggest shopping day of the year, hoping it will go unnoticed. While the report highlights the growing cost of doing nothing, Donald Trump insists on doing exactly that: nothing.

We can expect more reports of this type as scientists join the dots of the global phenomenon we are experiencing: the stronger hurricanes, heat waves, fires and floods ravaging the planet are not a coincidence or bad luck, but are instead the result of a climate catastrophe. The mountain ranges in the west of the country retain less snow throughout the year and threaten the water supply of their basins. Coral reefs in the Caribbean, Hawaii, Florida and the Pacific territories are being bleached, seriously threatening the ecosystems they shelter.

Fires devour increasingly larger areas in seasons that are getting longer and longer. Alaska, the only arctic state in the country, is undergoing rapid warming that is drastically changing its ecosystem, melting its coastlines and its permafrost tundra. And the Carolinas are still underwater from flooding brought on by Hurricane Florence.

The 1,600-page report is the result of the collaboration of 13 federal agencies: more than a thousand people, including three hundred leading scientists in the field. It is not a report to take lightly or to dismiss as alarmist, unless you are irresponsible, an imbecile, or both.

The magnitude of the problem requires a broad consensus to launch immediate action. Immediate means now, not in 2040. With the right measures we can still produce tangible effects that will improve the situation: as we let time go by, this will be nigh impossible to achieve and the cost beyond calculation. Failing to take immediate action will mean greater impact that will be harder to counter.

We have to grasp this and stop making excuses: we’re no longer talking problems for our grandchildren, but effects we are all going to witness within our lifespan. Meanwhile, irresponsible sections of society prefer to look the other way, dismiss the experts, drag their feet, come up with unsustainable arguments or just plain lies: but the simple truth is that the catastrophe is already unfolding around us.

Thanx Enrique Dans

Crusader Jenny , Nanook & Knight Mika

Friday, November 23, 2018

Climate Change Made Recent Hurricanes Wetter. And They May Get Worse

By Mindy Weisberger, Senior Writer | November 14, 2018

Captured by the GOES-16 satellite on Aug. 25, 2017, this image shows Hurricane Harvey as it reached its peak intensity — Category 4 — with maximum sustained winds of 130 mph.Credit: NESDIS

Some of the biggest storms in recent years were fueled by climate change, which increased the amount of their drenching rainfall. Future storms could be even windier, wetter — and potentially more destructive — according to a new study.

Researchers evaluated 15 tropical cyclones (which are called hurricanes when they form in the Atlantic) from the past decade and then simulated how the storms would have performed during preindustrial times, prior to the advent of recent climate change. They also peered into possible future scenarios, modeling what the storms might look like if they took shape during the late 21st century, should Earth's climate continue to warm.

Some hurricanes dumped up to 10 percent more rainfall as a result of climate change, and similar storms in the coming decades could deliver 30 percent more rainfall, the simulations revealed. [In Photos: Hurricane Maria Seen from Space]

The scientists' findings, published online today (Nov. 14) in the journal Nature, paint a sobering picture of a future marked by supercharged hurricane seasons.

In simulations that required millions of hours of computing time, the researchers investigated the role that a warming climate could play in hurricane winds and rainfall, looking at factors such as greenhouse gas concentrations, humidity and temperature variations in the air and in ocean water. They found that hurricane rainfall increased under climate-change scenarios, with Hurricanes Katrina, Irma and Maria producing about 5 to 10 percent more rain than they might have generated under preindustrial conditions.

Wind speeds for storms in the recent past, on the other hand, would probably have been more or less the same at the time of preindustrial Earth, according to the study. However, future storms will likely become windier, with peak wind speeds rising by as much as 33 mph (53 km/h). Rainfall is also predicted to increase in hurricanes by about 25 to 30 percent, if present-day emissions continue unchecked, the scientists reported.

Warming oceans are already recognized as a fuel source for more intense hurricane seasons. And rapidly accumulating evidence shows how climate change is directly affecting individual storms. In September, climate change was identified as a contributor to Hurricane Florence, with scientists estimating that the storm produced 50 percent more rain than it would have in a preindustrial world.

"We're already starting to see anthropogenic factors influencing tropical cyclone rainfall," lead study author Christina Patricola, a research scientist with the Climate and Ecosystem Sciences Division at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, said in a statement.

"And our simulations strongly indicate that as time goes on we can expect to see even greater increases in rainfall," Patricola added.

Urbanization raises the risk

More rainfall during seasonal hurricanes brings a greater risk of flooding to regions near coastlines. But the hazards of coastal living can also be intensified by another factor — human transformation of rural and suburban areas into more urban environments, according to another study, also published today in the journal Nature.

Researchers modeled simulations of Harvey's rainfall and flooding, measuring how Houston might have been affected if the city's urban development had stalled in the 1950s. They found that urbanization in Houston made the disastrous impacts of 2017's Hurricane Harvey even more damaging.

By comparing the simulations to Harvey's real impact in 2017, the scientists discovered that urbanization significantly increased how much rain fell during the storm and also increased the risk of flooding. New buildings in the city changed the airflow over Houston, leading to heavier precipitation; at the same time, more asphalt and concrete cover likely raised the risk of flooding.

Overall, the researchers found that urbanization in Houston increased the probability of extreme flooding from Harvey "by about 21 times." Climate modelers and urban planners alike therefore need to address and confront the threats faced by growing cities that are vulnerable to extreme precipitation, the study authors concluded.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger , Senior Writer

Knight Man

Captured by the GOES-16 satellite on Aug. 25, 2017, this image shows Hurricane Harvey as it reached its peak intensity — Category 4 — with maximum sustained winds of 130 mph.Credit: NESDIS

Some of the biggest storms in recent years were fueled by climate change, which increased the amount of their drenching rainfall. Future storms could be even windier, wetter — and potentially more destructive — according to a new study.

Researchers evaluated 15 tropical cyclones (which are called hurricanes when they form in the Atlantic) from the past decade and then simulated how the storms would have performed during preindustrial times, prior to the advent of recent climate change. They also peered into possible future scenarios, modeling what the storms might look like if they took shape during the late 21st century, should Earth's climate continue to warm.

Some hurricanes dumped up to 10 percent more rainfall as a result of climate change, and similar storms in the coming decades could deliver 30 percent more rainfall, the simulations revealed. [In Photos: Hurricane Maria Seen from Space]

The scientists' findings, published online today (Nov. 14) in the journal Nature, paint a sobering picture of a future marked by supercharged hurricane seasons.

In simulations that required millions of hours of computing time, the researchers investigated the role that a warming climate could play in hurricane winds and rainfall, looking at factors such as greenhouse gas concentrations, humidity and temperature variations in the air and in ocean water. They found that hurricane rainfall increased under climate-change scenarios, with Hurricanes Katrina, Irma and Maria producing about 5 to 10 percent more rain than they might have generated under preindustrial conditions.

Wind speeds for storms in the recent past, on the other hand, would probably have been more or less the same at the time of preindustrial Earth, according to the study. However, future storms will likely become windier, with peak wind speeds rising by as much as 33 mph (53 km/h). Rainfall is also predicted to increase in hurricanes by about 25 to 30 percent, if present-day emissions continue unchecked, the scientists reported.

Warming oceans are already recognized as a fuel source for more intense hurricane seasons. And rapidly accumulating evidence shows how climate change is directly affecting individual storms. In September, climate change was identified as a contributor to Hurricane Florence, with scientists estimating that the storm produced 50 percent more rain than it would have in a preindustrial world.

"We're already starting to see anthropogenic factors influencing tropical cyclone rainfall," lead study author Christina Patricola, a research scientist with the Climate and Ecosystem Sciences Division at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, said in a statement.

"And our simulations strongly indicate that as time goes on we can expect to see even greater increases in rainfall," Patricola added.

Urbanization raises the risk

More rainfall during seasonal hurricanes brings a greater risk of flooding to regions near coastlines. But the hazards of coastal living can also be intensified by another factor — human transformation of rural and suburban areas into more urban environments, according to another study, also published today in the journal Nature.

Researchers modeled simulations of Harvey's rainfall and flooding, measuring how Houston might have been affected if the city's urban development had stalled in the 1950s. They found that urbanization in Houston made the disastrous impacts of 2017's Hurricane Harvey even more damaging.

By comparing the simulations to Harvey's real impact in 2017, the scientists discovered that urbanization significantly increased how much rain fell during the storm and also increased the risk of flooding. New buildings in the city changed the airflow over Houston, leading to heavier precipitation; at the same time, more asphalt and concrete cover likely raised the risk of flooding.

Overall, the researchers found that urbanization in Houston increased the probability of extreme flooding from Harvey "by about 21 times." Climate modelers and urban planners alike therefore need to address and confront the threats faced by growing cities that are vulnerable to extreme precipitation, the study authors concluded.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger , Senior Writer

Knight Man

Monday, November 19, 2018

Warmer, Wetter Than Usual Winter Headed for Much of US

By Laura Geggel, Senior Writer | November 16, 2018

Credit: Shutterstock

Just over half of the United States has no need to fear an exceptionally frigid, frozen winter in the coming months — instead, they'll likely experience a warmer and wetter winter than usual, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center.

In the three coming months — December, January and February — the West Coast, the Mountain states and chunks of the Midwest and Northeast (although not New York or Boston) are all forecast to have above-normal temperatures for the season, as well as increased precipitation (meaning rain and snow), the Climate Prediction Center announced at a news conference yesterday (Nov. 15).

The warm and wet winter is due, in part, to weather patterns such as El Niño and decadal changes in ocean patterns , as well as climate change, said Stephen Baxter, a meteorologist and seasonal forecaster at the NOAA Climate Prediction Center. [Winter Wonderland: Images of Stunning Snowy Landscapes]

During the news conference, Baxter first presented the weather outlook for December, which is shown below. Areas that are red, orange and yellow are predicted to have above-normal winter temperatures, he said. The blue region covering the Great Lakes region is expected to be cooler than usual. Meanwhile, the white-colored areas in the United States are expected to have typical winter temperatures.

The December 2018 outlook for average temperature (left) and precipitation (right).Credit: NOAA

As for December precipitation (the map on the right), the green swaths over parts of California, the Mountain states and the Southeast indicate above-normal rainfall, while the yellow patches going diagonally from Texas to Maine show that those regions will likely receive less precipitation than average.

The December-January-February temperature outlook is slightly different. Notice how — in the map shown below — the above-average temperatures still cover Alaska and much of the American West and Midwest, but that the predicted cold spot over the Great Lakes area disappears.

The December, January and February average for temperature (left) and precipitation (right).Credit: NOAA

The three-month precipitation outlook shows a different story. It's predicted that the lower tier of the United States will get more than the average precipitation, while parts of the Midwest and the Great Lakes regions will get below-normal precipitation.

It appears that El Niño is partly responsible for the warmer temperatures on the West Coast. El Niño happens when the equatorial Pacific Ocean warms, which in turn sloshes warm water and humid air east toward the Americas. El Niño also tends to lead to the easternly extension of the jetstream from southeast of Japan to across the Pacific Basin, and to a low-pressure system in the northeast Pacific, Baxter said.

All of these factors tend to "lead to anomalous warm air convection in western United States and southern Alaska," Baxter said. (In another words, you have warm air where you normally wouldn't.) "And so you tend to have less cold air intrusions there. You also tend to have more storm activity across the southern tier of the U.S., and so that is that increased stormtrack there."

Climate change is also playing a role in this winter's weather, although it can be difficult to suss just how much, Baxter said. That's because so many factors influence the weather, such as increased greenhouse gas emissions and decadal changes in ocean patterns , and so it can be challenging to determine which signals are coming from where.

"Part of the challenge is just disentangling these things," Baxter said. "Climate now is higher than the fixed 30-year base period that we've used … and a good portion of that is long-term climate change."

Instead of taking the average of the past 30 years, climatologists are finding they can get a more accurate picture of the current climate by taking an average of just the past 15 years. And, according to NOAA and NASA, the five warmest years on record happened in the 2010s, while the 10 warmest years on record have occurred since 1998, Climate Central reported earlier this year.

Thanx Laura eggel . Senior Writer

Originally published on Live Science

Knight Sha

Credit: Shutterstock

Just over half of the United States has no need to fear an exceptionally frigid, frozen winter in the coming months — instead, they'll likely experience a warmer and wetter winter than usual, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center.

In the three coming months — December, January and February — the West Coast, the Mountain states and chunks of the Midwest and Northeast (although not New York or Boston) are all forecast to have above-normal temperatures for the season, as well as increased precipitation (meaning rain and snow), the Climate Prediction Center announced at a news conference yesterday (Nov. 15).

The warm and wet winter is due, in part, to weather patterns such as El Niño and decadal changes in ocean patterns , as well as climate change, said Stephen Baxter, a meteorologist and seasonal forecaster at the NOAA Climate Prediction Center. [Winter Wonderland: Images of Stunning Snowy Landscapes]

During the news conference, Baxter first presented the weather outlook for December, which is shown below. Areas that are red, orange and yellow are predicted to have above-normal winter temperatures, he said. The blue region covering the Great Lakes region is expected to be cooler than usual. Meanwhile, the white-colored areas in the United States are expected to have typical winter temperatures.

The December 2018 outlook for average temperature (left) and precipitation (right).Credit: NOAA

As for December precipitation (the map on the right), the green swaths over parts of California, the Mountain states and the Southeast indicate above-normal rainfall, while the yellow patches going diagonally from Texas to Maine show that those regions will likely receive less precipitation than average.

The December-January-February temperature outlook is slightly different. Notice how — in the map shown below — the above-average temperatures still cover Alaska and much of the American West and Midwest, but that the predicted cold spot over the Great Lakes area disappears.

The December, January and February average for temperature (left) and precipitation (right).Credit: NOAA

The three-month precipitation outlook shows a different story. It's predicted that the lower tier of the United States will get more than the average precipitation, while parts of the Midwest and the Great Lakes regions will get below-normal precipitation.

It appears that El Niño is partly responsible for the warmer temperatures on the West Coast. El Niño happens when the equatorial Pacific Ocean warms, which in turn sloshes warm water and humid air east toward the Americas. El Niño also tends to lead to the easternly extension of the jetstream from southeast of Japan to across the Pacific Basin, and to a low-pressure system in the northeast Pacific, Baxter said.

All of these factors tend to "lead to anomalous warm air convection in western United States and southern Alaska," Baxter said. (In another words, you have warm air where you normally wouldn't.) "And so you tend to have less cold air intrusions there. You also tend to have more storm activity across the southern tier of the U.S., and so that is that increased stormtrack there."

Climate change is also playing a role in this winter's weather, although it can be difficult to suss just how much, Baxter said. That's because so many factors influence the weather, such as increased greenhouse gas emissions and decadal changes in ocean patterns , and so it can be challenging to determine which signals are coming from where.

"Part of the challenge is just disentangling these things," Baxter said. "Climate now is higher than the fixed 30-year base period that we've used … and a good portion of that is long-term climate change."

Instead of taking the average of the past 30 years, climatologists are finding they can get a more accurate picture of the current climate by taking an average of just the past 15 years. And, according to NOAA and NASA, the five warmest years on record happened in the 2010s, while the 10 warmest years on record have occurred since 1998, Climate Central reported earlier this year.

Thanx Laura eggel . Senior Writer

Originally published on Live Science

Knight Sha

Friday, November 16, 2018

Tuesday, November 13, 2018

Glaciers Created a Huge 'Flour' Dust Storm in Greenland

By Rafi Letzter, Staff Writer | November 2, 2018

A large plume of "glacier flour" blew off of Greenland Sept. 29.Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

If you're in Greenland and a strange cloud darkens the sky, that cloud might be made up of something scientists call "glacier flour."

Researchers have written and speculated about glacier-flour dust storms in Greenland for a long time, according to NASA. But it took until this September for investigators to spot such a massive plume of the elusive dust forming and drifting 80 miles (130 kilometers) northwest of the far-northern village of Ittoqqortoormiit. Glacier flour is a fine dust created when glaciers pulverize rocks, NASA wrote. While satellites had occasionally spotted smaller storms of the stuff, this one was "by far the largest."

"We have seen a few examples of small dust events before this one, but they are quite difficult to spot with satellites because of cloud cover," Joanna Bullard, a professor of physical geography at Loughborough University in the United Kingdom, said in a NASA statement. "When dust events do happen, field data from Iceland and West Greenland indicate that they rarely last longer than two days." [7 Crazy Facts About Dust Storms]

The flour storm formed when a summer floodplain in the region dried out with late September's colder weather, leaving behind a large deposit of sediment carried south from more-northern glaciers.

NASA satellites watched the floodplain become grayer and grayer as it dried out, then saw the plume form when strong winds swept through the area on Sept. 29.

A composite image shows how the plume emerged over the course of several days.Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

According to NASA, storms like this are interesting because researchers just don't know much about them or how they affect the climate. While large dust storms found closer to the equator have known climate impacts, the role of glacial flour remains a mystery.

Originally published on Live Science.

Thanx Rafi letzter

Knight Jonny

A large plume of "glacier flour" blew off of Greenland Sept. 29.Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

If you're in Greenland and a strange cloud darkens the sky, that cloud might be made up of something scientists call "glacier flour."

Researchers have written and speculated about glacier-flour dust storms in Greenland for a long time, according to NASA. But it took until this September for investigators to spot such a massive plume of the elusive dust forming and drifting 80 miles (130 kilometers) northwest of the far-northern village of Ittoqqortoormiit. Glacier flour is a fine dust created when glaciers pulverize rocks, NASA wrote. While satellites had occasionally spotted smaller storms of the stuff, this one was "by far the largest."

"We have seen a few examples of small dust events before this one, but they are quite difficult to spot with satellites because of cloud cover," Joanna Bullard, a professor of physical geography at Loughborough University in the United Kingdom, said in a NASA statement. "When dust events do happen, field data from Iceland and West Greenland indicate that they rarely last longer than two days." [7 Crazy Facts About Dust Storms]

The flour storm formed when a summer floodplain in the region dried out with late September's colder weather, leaving behind a large deposit of sediment carried south from more-northern glaciers.