The unprecedented regulatory slowdown and rollbacks at the Environmental Protection Agency

The mandate of the head of the Environmental Protection Agency is to protect human health and enforce environmental regulations.

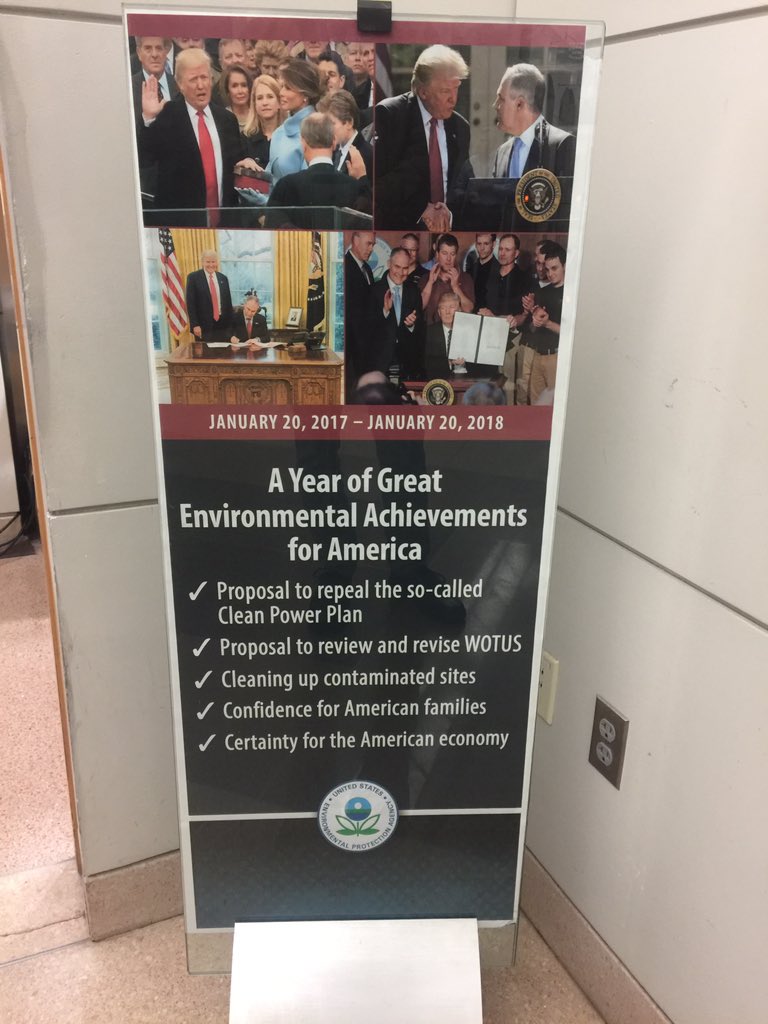

Yet since he was confirmed last February, EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt has worked to stall or roll back this core function of his agency, efforts he’s now celebrating with posters:

He’s also taken some highly unusual, even paranoid, precautions, arming himself with a 24/7 security detail, building a $25,000 secret phone booth in his office, spending $9,000 to sweep his office for surveillance bugs, and hiding his schedule from the public. When one employee turned one of the celebratory posters around, Pruitt assigned a worker to look through security camera records to see who did it.

Pruitt’s posters are a list of the regulatory rollbacks he’s delivered to his allies in coal, oil, gas, and chemicals industries. These gifts include the reversal of a ban on chlorpyrifos, a pesticide linked to developmental problems in children.

Some of the biggest changes Pruitt has made at the EPA have come by not doing anything at all. He’s steering the EPA’s work at an agonizingly slow pace, delaying and slowing the implementation of laws and running interference for many of the sectors EPA is supposed to regulate.

With more staff and funding cuts looming, even fewer toxic chemicals and other environmental hazards will be banned or regulated, and the laws that protect Americans against them won’t be enforced.

“People will get sick and die,” Christine Todd Whitman, who served as EPA administrator under President George W. Bush, told Vox. “It’s that simple.” Some 230,000 Americans already die each year due to hazardous chemical exposures. “You stop enforcing those regulations and that number will go way up,” she said.

Chaos at the White House and on Capitol Hill has provided Pruitt cover for his activities, namely deregulating and dismantling the Environmental Protection Agency piece by piece. He has quietly positioned himself as the greatest threat to the EPA in its entire existence. But some lawmakers and the courts are starting to catch onto him. Since the EPA’s inception, it’s been the judiciary that’s again and again beaten back attempts to undermine the agency from the inside. This year is again shaping up to be momentous.

States are now suing to block Pruitt’s regulatory changes, and federal judges are starting to force him to speed up. Pruitt will have to choose between knock-down, drag-out legal fights to deliver for his allies in industry or fold and grudgingly enforce environmental rules. Whatever he decides, Congress, courts, industry, and activists will be watching.

Pruitt can’t simply repeal all the rules he doesn’t like, so he’s had to embrace a different strategy: stall. By stalling, Pruitt can effectively shift policy by doing nothing. If he leaves regulations in limbo or delays their implementation, industries get relief from environmental rules while the EPA retains plausible deniability.

Here are some of the EPA's actual achievments:

- The EPA announced it was seeking a two-year delay in implementing the 2015 Clean Water Rule, which defines the waterways that are regulated by the agency under the Clean Water Act.

- In May, the EPA stalled on tracking the health impacts of more than a dozen hazardous chemicals at the behest of a Trump appointee at the agency, Nancy Beck.

- The agency has said nothing and done nothing about counties that failed to meet new ozone standards by an October 2017 deadline and now face fines.

- Environmental law enforcement has declined; the rules are simply not being followed and the EPA ignores that fact.. By September, the Trump administration launched 30 percent fewer cases and collected about 60 percent fewer fines than in the same period under President Obama.

- The EPA delayed regulations on dangerous solvents like methylene chloride, a paint stripper, that were already on track to be banned, instead moving the process to “long term action.”

- The EPA asked for a six-year schedule to review 17-year-old regulations on lead paint.

- The implementation date of new safety procedures at chemical plants to prevent explosions and spills was pushed back to 2019.

- Pruitt issued a directive to end “Sue & Settle,” a legal strategy that fast-tracks settlements for litigation filed against the EPA to force the agency to do its job. The agency will spend more time in courts fighting cases that it’s likely to lose.

- The agency’s enforcement division now has to get approval from headquarters before investigating violations of environmental regulations, which slows down efforts to catch violators of laws like the Clean Water Act.

Losing the environmental protections established by the EPA could harm millions of Americans

The EPA is essentially an environmental public health agency. Its regulations directly affect millions of Americans as it diagnoses ailments in the air, water, and soil, to name a few, and prescribes solutions.

It has had a pretty great track record.

The Clean Air Act, for example, reduced conventional air pollutants by 70 percent since 1970. Substances like ozone, carbon monoxide, and lead have dangerous consequences for human health like heart attacks, strokes, and respiratory arrests.

According to one estimate, the legislation prevents 184,000 premature deaths each year and has saved $22 trillion in health care costs over a period of 20 years.

But enforcing these rules bears a cost as well, and critics say that continuing to make many of these regulations stick costs businesses more and more to comply with them. This is the main rationale for the White House’s aim to cut back on “job-killing” regulations.

Many of these regulations took years to put together and will require years to take apart, endeavors that would likely not resolve until well into President Trump’s second term.

The courts are losing their patience with the agency and are now forcing Pruitt’s hand

Federal courts don’t agree with Pruitt's deconstruction of the EPA and are no longer deferring to the new administration. Courts have already blocked the EPA’s efforts to suspend rules on methane emissions and denied the EPA’s request to spend years researching lead paint, instead giving the agency 90 days to come up with a new regulation.

“I think you’re going to see courts get more involved in the work of the agency,” said former EPA general counsel Avi Garbow, who served under President Obama. “That judicial patience cannot be counted on forever.”

Some states are suing the department for not controlling air pollution moving across state lines. Some of the scientists who were ousted from the EPA’s advisory boards are now suing the agency, arguing that their removal violates the Federal Advisory Committee Act. Public lawsuits are also going forward to try to force the agency’s hand to fight climate change.

There are also some regulations Pruitt supports. He wants to remove lead from all drinking water in the United States in 10 years and has started taking comments on revising rules for water pipes. He also wants to control leaks of methane, the primary component in natural gas and a potent greenhouse gas.

All the while, lawmakers are also growing increasingly suspicious about Pruitt’s activities and are launching investigations. Michael Dourson, a former chemical industry consultant who was nominated to lead the EPA’s Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention, withdrew his name from consideration after facing stiff opposition from Congress.

The laws that govern the EPA require action, and whether those demands come from Congress, the courts, or constituents, the agency needs to produce results that stand up to legal challenges from all sides.

The goal is not to give industries a free pass from all responsibility for the environment, but to protect American lives. Pruitt may soon find out that doing nothing, or even very little, is not an option.