A house set alight by the Camp Fire in Paradise, Calif., on Thursday. The fast-spreading fire has been burning 80 acres per minute.CreditCreditNoah Berger/Associated Press

By Kendra Pierre-Louis Nov. 9, 2018

A pregnant woman went into labor while being evacuated. Videos showed dozens of harrowing drives through fiery landscapes. Pleas appeared on social media seeking the whereabouts of loved ones. Survivors of a mass shooting were forced to flee approaching flames.

This has been California since the Camp Fire broke out early Thursday morning, burning 80 acres per minute and devastating the northern town of Paradise. Later in the day, the Woolsey Fire broke out to the south in Ventura and Los Angeles Counties, prompting the evacuation of all of Malibu.

What is it about California that makes wildfires so catastrophic? There are four key ingredients.

The (changing) climate

The first is California’s climate.

“Fire, in some ways, is a very simple thing,” said Park Williams, a bioclimatologist at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. “As long as stuff is dry enough and there’s a spark, then that stuff will burn.”

California, like much of the West, gets most of its moisture in the fall and winter. Its vegetation then spends much of the summer slowly drying out because of a lack of rainfall and warmer temperatures. That vegetation then serves as kindling for fires.

But while California’s climate has always been fire prone, the link between climate change and bigger fires is inextricable. “Behind the scenes of all of this, you’ve got temperatures that are about two to three degrees Fahrenheit warmer now than they would’ve been without global warming,” Dr. Williams said. That dries out vegetation even more, making it more likely to burn.

California’s fire record dates back to 1932; of the 10 largest fires since then, nine have occurred since 2000, five since 2010 and two this year alone, including the Mendocino Complex Fire, the largest in state history.

“In pretty much every single way, a perfect recipe for fire is just kind of written in California,” Dr. Williams said. “Nature creates the perfect conditions for fire, as long as people are there to start the fires. But then climate change, in a few different ways, seems to also load the dice toward more fire in the future.”

California Fires Map ; Tracking the spread

Wildfires have burned in California near the Sierra Nevada foothills and the Los Angeles shoreline , engulfing nearly 250,000 acres November 11 , 2018 .

People

Even if the conditions are right for a wildfire, you still need something or someone to ignite it. Sometimes the trigger is nature, like a lightning strike, but more often than not humans are responsible.

“Many of these large fires that you’re seeing in Southern California and impacting the areas where people are living are human-caused,” said Nina S. Oakley, an assistant research professor of atmospheric science at the Desert Research Institute.

Deadly fires in and around Sonoma County last year were started by downed power lines. This year’s Carr Fire, the state’s sixth-largest on record, started when a truck blew out its tire and its rim scraped the pavement, sending out sparks.

“California has a lot of people and a really long dry season,” Dr. Williams said. “People are always creating possible sparks, and as the dry season wears on and stuff is drying out more and more, the chance that a spark comes off a person at the wrong time just goes up. And that’s putting aside arson.”

There’s another way people have contributed to wildfires: in their choices of where to live. People are increasingly moving into areas near forests, known as the urban-wildland interface, that are inclined to burn.

“In Nevada, we have many, many large fires, but typically they’re burning open spaces,” Dr. Oakley said. “They’re not burning through neighborhoods.”

What on Earth Is Going On?

Patients were evacuated from the Feather River Hospital in Paradise, Calif.Credit Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Fire suppression

It’s counterintuitive, but the United States’ history of suppressing wildfires has actually made present-day wildfires worse.

“For the last century we fought fire, and we did pretty well at it across all of the Western United States,” Dr. Williams said. “And every time we fought a fire successfully, that means that a bunch of stuff that would have burned didn’t burn. And so over the last hundred years we’ve had an accumulation of plants in a lot of areas.

“And so in a lot of California now when fires start, those fires are burning through places that have a lot more plants to burn than they would have if we had been allowing fires to burn for the last hundred years.”

In recent years, the United States Forest Service has been trying to rectify the previous practice through the use of prescribed or “controlled” burns.

The Santa Ana winds

Each fall, strong gusts known as the Santa Ana winds bring dry air from the Great Basin area of the West into Southern California, said Fengpeng Sun, an assistant professor in the department of geosciences at the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Dr. Sun is a co-author of a 2015 study that suggests that California has two distinct fire seasons. One, which runs from June through September and is driven by a combination of warmer and drier weather, is the Western fire season that most people think of. Those wildfires tend to be more inland, in higher-elevation forests.

But Dr. Sun and his co-authors also identified a second fire season that runs from October through April and is driven by the Santa Ana winds. Those fires tend to spread three times faster and burn closer to urban areas, and they were responsible for 80 percent of the economic losses over two decades beginning in 1990.

[Minorities are most vulnerable when wildfires strike in the United States, a study found.]

It’s not just that the Santa Ana winds dry out vegetation; they also move embers around, spreading fires.

If the fall rains, which usually begin in October, fail to arrive on time, as they did this year, the winds can make already dry conditions even drier. During an average October, Northern California can get more than two inches of rain, according to Derek Arndt, chief of the monitoring branch at the National Centers for Environmental Information, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. This year, in some places, less than half that amount fell.

“None of these are like, record-breaking, historically dry for October,” Dr. Arndt said. “But they’re all on the dry side of history.”

Kendra Pierre-Louis is a reporter on the climate team. Before joining The Times in 2017, she covered science and the environment for Popular Science. @kendrawrites

Thanx Kendra Pierre-Louis

Knight Jonny

Friday, November 30, 2018

Wednesday, November 28, 2018

Dead whale found with 13 pounds of plastic in stomach

Nov. 21, 2018 - A dead sperm whale washed ashore in eastern Indonesia with 13 pounds of plastic in its stomach. The trash included 115 drinking cups, 25 plastic bags, plastic bottles, two flip-flops, and more than 1,000 pieces of string. The whale’s exact cause of death is unknown, but observers say the whale may highlight the global plastic pollution problem.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch

The findings from the two expeditions, found that the patch covers 1.6 million square kilometers (617,000 sq. miles) with a concentration of 10–100 kg per square kilometer. They estimate an 80,000 metric tons in the patch, with 1.8 trillion plastic pieces, out of which 92% of the mass is to be found in objects larger than 0.5 centimeters.

IT'S TWICE THE SIZE OF TEXAS

Closeup below

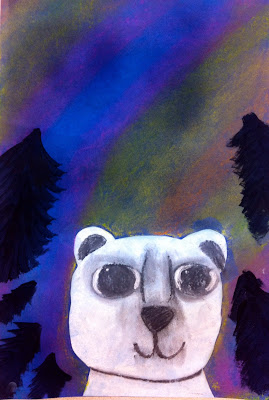

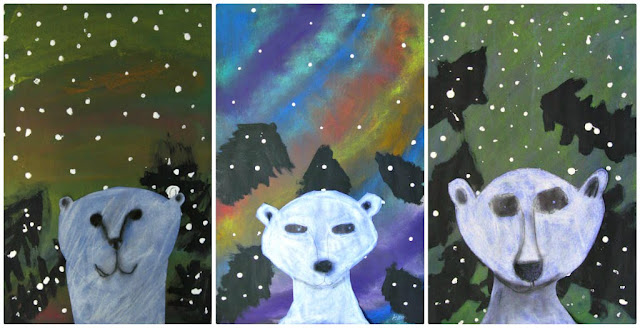

Moto - The Wanna-be Knight

Jake and Moto

Moto is Mika's brother. He's jealous because he wants to be a knight too. The problem is Moto is not cute at all and Mika doesn't like him much.

Monday, November 26, 2018

Sunday, November 25, 2018

When Will We Accept That Climate Change Is Real? /sites/enriquedans/

Enrique Dans Contributor November 18 , 2018

Leadership Strategy Teaching and consulting in the innovation field since 1990

A street sign sits submerged in floodwater after Hurricane Florence hit in Bergaw, North Carolina, U.S., on Friday, Sept. 21, 2018. President Donald Trump lauded the federal response to Hurricane Florence on Wednesday as he began a tour of areas in North and South Carolina hit over the weekend by high winds and torrential rain. Photographer: Callaghan O'Hare/Bloomberg© 2018 Bloomberg Finance LP

The US National Climate Assessment (NCA) has just published a report on the impact, risks and adaptation of the United States to climate change, and concludes, radically contradicting the opinion of the country’s irresponsible president, that the impact is already being felt and will be devastating in the near future, involving from tens of thousands of deaths to hundreds of billions of dollars in damages. And the Trump administration’s reaction to the report? To publish it on Black Friday, the biggest shopping day of the year, hoping it will go unnoticed. While the report highlights the growing cost of doing nothing, Donald Trump insists on doing exactly that: nothing.

We can expect more reports of this type as scientists join the dots of the global phenomenon we are experiencing: the stronger hurricanes, heat waves, fires and floods ravaging the planet are not a coincidence or bad luck, but are instead the result of a climate catastrophe. The mountain ranges in the west of the country retain less snow throughout the year and threaten the water supply of their basins. Coral reefs in the Caribbean, Hawaii, Florida and the Pacific territories are being bleached, seriously threatening the ecosystems they shelter.

Fires devour increasingly larger areas in seasons that are getting longer and longer. Alaska, the only arctic state in the country, is undergoing rapid warming that is drastically changing its ecosystem, melting its coastlines and its permafrost tundra. And the Carolinas are still underwater from flooding brought on by Hurricane Florence.

The 1,600-page report is the result of the collaboration of 13 federal agencies: more than a thousand people, including three hundred leading scientists in the field. It is not a report to take lightly or to dismiss as alarmist, unless you are irresponsible, an imbecile, or both.

The magnitude of the problem requires a broad consensus to launch immediate action. Immediate means now, not in 2040. With the right measures we can still produce tangible effects that will improve the situation: as we let time go by, this will be nigh impossible to achieve and the cost beyond calculation. Failing to take immediate action will mean greater impact that will be harder to counter.

We have to grasp this and stop making excuses: we’re no longer talking problems for our grandchildren, but effects we are all going to witness within our lifespan. Meanwhile, irresponsible sections of society prefer to look the other way, dismiss the experts, drag their feet, come up with unsustainable arguments or just plain lies: but the simple truth is that the catastrophe is already unfolding around us.

Thanx Enrique Dans

Crusader Jenny , Nanook & Knight Mika

Leadership Strategy Teaching and consulting in the innovation field since 1990

A street sign sits submerged in floodwater after Hurricane Florence hit in Bergaw, North Carolina, U.S., on Friday, Sept. 21, 2018. President Donald Trump lauded the federal response to Hurricane Florence on Wednesday as he began a tour of areas in North and South Carolina hit over the weekend by high winds and torrential rain. Photographer: Callaghan O'Hare/Bloomberg© 2018 Bloomberg Finance LP

The US National Climate Assessment (NCA) has just published a report on the impact, risks and adaptation of the United States to climate change, and concludes, radically contradicting the opinion of the country’s irresponsible president, that the impact is already being felt and will be devastating in the near future, involving from tens of thousands of deaths to hundreds of billions of dollars in damages. And the Trump administration’s reaction to the report? To publish it on Black Friday, the biggest shopping day of the year, hoping it will go unnoticed. While the report highlights the growing cost of doing nothing, Donald Trump insists on doing exactly that: nothing.

We can expect more reports of this type as scientists join the dots of the global phenomenon we are experiencing: the stronger hurricanes, heat waves, fires and floods ravaging the planet are not a coincidence or bad luck, but are instead the result of a climate catastrophe. The mountain ranges in the west of the country retain less snow throughout the year and threaten the water supply of their basins. Coral reefs in the Caribbean, Hawaii, Florida and the Pacific territories are being bleached, seriously threatening the ecosystems they shelter.

Fires devour increasingly larger areas in seasons that are getting longer and longer. Alaska, the only arctic state in the country, is undergoing rapid warming that is drastically changing its ecosystem, melting its coastlines and its permafrost tundra. And the Carolinas are still underwater from flooding brought on by Hurricane Florence.

The 1,600-page report is the result of the collaboration of 13 federal agencies: more than a thousand people, including three hundred leading scientists in the field. It is not a report to take lightly or to dismiss as alarmist, unless you are irresponsible, an imbecile, or both.

The magnitude of the problem requires a broad consensus to launch immediate action. Immediate means now, not in 2040. With the right measures we can still produce tangible effects that will improve the situation: as we let time go by, this will be nigh impossible to achieve and the cost beyond calculation. Failing to take immediate action will mean greater impact that will be harder to counter.

We have to grasp this and stop making excuses: we’re no longer talking problems for our grandchildren, but effects we are all going to witness within our lifespan. Meanwhile, irresponsible sections of society prefer to look the other way, dismiss the experts, drag their feet, come up with unsustainable arguments or just plain lies: but the simple truth is that the catastrophe is already unfolding around us.

Thanx Enrique Dans

Crusader Jenny , Nanook & Knight Mika

Friday, November 23, 2018

Climate Change Made Recent Hurricanes Wetter. And They May Get Worse

By Mindy Weisberger, Senior Writer | November 14, 2018

Captured by the GOES-16 satellite on Aug. 25, 2017, this image shows Hurricane Harvey as it reached its peak intensity — Category 4 — with maximum sustained winds of 130 mph.Credit: NESDIS

Some of the biggest storms in recent years were fueled by climate change, which increased the amount of their drenching rainfall. Future storms could be even windier, wetter — and potentially more destructive — according to a new study.

Researchers evaluated 15 tropical cyclones (which are called hurricanes when they form in the Atlantic) from the past decade and then simulated how the storms would have performed during preindustrial times, prior to the advent of recent climate change. They also peered into possible future scenarios, modeling what the storms might look like if they took shape during the late 21st century, should Earth's climate continue to warm.

Some hurricanes dumped up to 10 percent more rainfall as a result of climate change, and similar storms in the coming decades could deliver 30 percent more rainfall, the simulations revealed. [In Photos: Hurricane Maria Seen from Space]

The scientists' findings, published online today (Nov. 14) in the journal Nature, paint a sobering picture of a future marked by supercharged hurricane seasons.

In simulations that required millions of hours of computing time, the researchers investigated the role that a warming climate could play in hurricane winds and rainfall, looking at factors such as greenhouse gas concentrations, humidity and temperature variations in the air and in ocean water. They found that hurricane rainfall increased under climate-change scenarios, with Hurricanes Katrina, Irma and Maria producing about 5 to 10 percent more rain than they might have generated under preindustrial conditions.

Wind speeds for storms in the recent past, on the other hand, would probably have been more or less the same at the time of preindustrial Earth, according to the study. However, future storms will likely become windier, with peak wind speeds rising by as much as 33 mph (53 km/h). Rainfall is also predicted to increase in hurricanes by about 25 to 30 percent, if present-day emissions continue unchecked, the scientists reported.

Warming oceans are already recognized as a fuel source for more intense hurricane seasons. And rapidly accumulating evidence shows how climate change is directly affecting individual storms. In September, climate change was identified as a contributor to Hurricane Florence, with scientists estimating that the storm produced 50 percent more rain than it would have in a preindustrial world.

"We're already starting to see anthropogenic factors influencing tropical cyclone rainfall," lead study author Christina Patricola, a research scientist with the Climate and Ecosystem Sciences Division at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, said in a statement.

"And our simulations strongly indicate that as time goes on we can expect to see even greater increases in rainfall," Patricola added.

Urbanization raises the risk

More rainfall during seasonal hurricanes brings a greater risk of flooding to regions near coastlines. But the hazards of coastal living can also be intensified by another factor — human transformation of rural and suburban areas into more urban environments, according to another study, also published today in the journal Nature.

Researchers modeled simulations of Harvey's rainfall and flooding, measuring how Houston might have been affected if the city's urban development had stalled in the 1950s. They found that urbanization in Houston made the disastrous impacts of 2017's Hurricane Harvey even more damaging.

By comparing the simulations to Harvey's real impact in 2017, the scientists discovered that urbanization significantly increased how much rain fell during the storm and also increased the risk of flooding. New buildings in the city changed the airflow over Houston, leading to heavier precipitation; at the same time, more asphalt and concrete cover likely raised the risk of flooding.

Overall, the researchers found that urbanization in Houston increased the probability of extreme flooding from Harvey "by about 21 times." Climate modelers and urban planners alike therefore need to address and confront the threats faced by growing cities that are vulnerable to extreme precipitation, the study authors concluded.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger , Senior Writer

Knight Man

Captured by the GOES-16 satellite on Aug. 25, 2017, this image shows Hurricane Harvey as it reached its peak intensity — Category 4 — with maximum sustained winds of 130 mph.Credit: NESDIS

Some of the biggest storms in recent years were fueled by climate change, which increased the amount of their drenching rainfall. Future storms could be even windier, wetter — and potentially more destructive — according to a new study.

Researchers evaluated 15 tropical cyclones (which are called hurricanes when they form in the Atlantic) from the past decade and then simulated how the storms would have performed during preindustrial times, prior to the advent of recent climate change. They also peered into possible future scenarios, modeling what the storms might look like if they took shape during the late 21st century, should Earth's climate continue to warm.

Some hurricanes dumped up to 10 percent more rainfall as a result of climate change, and similar storms in the coming decades could deliver 30 percent more rainfall, the simulations revealed. [In Photos: Hurricane Maria Seen from Space]

The scientists' findings, published online today (Nov. 14) in the journal Nature, paint a sobering picture of a future marked by supercharged hurricane seasons.

In simulations that required millions of hours of computing time, the researchers investigated the role that a warming climate could play in hurricane winds and rainfall, looking at factors such as greenhouse gas concentrations, humidity and temperature variations in the air and in ocean water. They found that hurricane rainfall increased under climate-change scenarios, with Hurricanes Katrina, Irma and Maria producing about 5 to 10 percent more rain than they might have generated under preindustrial conditions.

Wind speeds for storms in the recent past, on the other hand, would probably have been more or less the same at the time of preindustrial Earth, according to the study. However, future storms will likely become windier, with peak wind speeds rising by as much as 33 mph (53 km/h). Rainfall is also predicted to increase in hurricanes by about 25 to 30 percent, if present-day emissions continue unchecked, the scientists reported.

Warming oceans are already recognized as a fuel source for more intense hurricane seasons. And rapidly accumulating evidence shows how climate change is directly affecting individual storms. In September, climate change was identified as a contributor to Hurricane Florence, with scientists estimating that the storm produced 50 percent more rain than it would have in a preindustrial world.

"We're already starting to see anthropogenic factors influencing tropical cyclone rainfall," lead study author Christina Patricola, a research scientist with the Climate and Ecosystem Sciences Division at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, said in a statement.

"And our simulations strongly indicate that as time goes on we can expect to see even greater increases in rainfall," Patricola added.

Urbanization raises the risk

More rainfall during seasonal hurricanes brings a greater risk of flooding to regions near coastlines. But the hazards of coastal living can also be intensified by another factor — human transformation of rural and suburban areas into more urban environments, according to another study, also published today in the journal Nature.

Researchers modeled simulations of Harvey's rainfall and flooding, measuring how Houston might have been affected if the city's urban development had stalled in the 1950s. They found that urbanization in Houston made the disastrous impacts of 2017's Hurricane Harvey even more damaging.

By comparing the simulations to Harvey's real impact in 2017, the scientists discovered that urbanization significantly increased how much rain fell during the storm and also increased the risk of flooding. New buildings in the city changed the airflow over Houston, leading to heavier precipitation; at the same time, more asphalt and concrete cover likely raised the risk of flooding.

Overall, the researchers found that urbanization in Houston increased the probability of extreme flooding from Harvey "by about 21 times." Climate modelers and urban planners alike therefore need to address and confront the threats faced by growing cities that are vulnerable to extreme precipitation, the study authors concluded.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger , Senior Writer

Knight Man

Monday, November 19, 2018

Warmer, Wetter Than Usual Winter Headed for Much of US

By Laura Geggel, Senior Writer | November 16, 2018

Credit: Shutterstock

Just over half of the United States has no need to fear an exceptionally frigid, frozen winter in the coming months — instead, they'll likely experience a warmer and wetter winter than usual, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center.

In the three coming months — December, January and February — the West Coast, the Mountain states and chunks of the Midwest and Northeast (although not New York or Boston) are all forecast to have above-normal temperatures for the season, as well as increased precipitation (meaning rain and snow), the Climate Prediction Center announced at a news conference yesterday (Nov. 15).

The warm and wet winter is due, in part, to weather patterns such as El Niño and decadal changes in ocean patterns , as well as climate change, said Stephen Baxter, a meteorologist and seasonal forecaster at the NOAA Climate Prediction Center. [Winter Wonderland: Images of Stunning Snowy Landscapes]

During the news conference, Baxter first presented the weather outlook for December, which is shown below. Areas that are red, orange and yellow are predicted to have above-normal winter temperatures, he said. The blue region covering the Great Lakes region is expected to be cooler than usual. Meanwhile, the white-colored areas in the United States are expected to have typical winter temperatures.

The December 2018 outlook for average temperature (left) and precipitation (right).Credit: NOAA

As for December precipitation (the map on the right), the green swaths over parts of California, the Mountain states and the Southeast indicate above-normal rainfall, while the yellow patches going diagonally from Texas to Maine show that those regions will likely receive less precipitation than average.

The December-January-February temperature outlook is slightly different. Notice how — in the map shown below — the above-average temperatures still cover Alaska and much of the American West and Midwest, but that the predicted cold spot over the Great Lakes area disappears.

The December, January and February average for temperature (left) and precipitation (right).Credit: NOAA

The three-month precipitation outlook shows a different story. It's predicted that the lower tier of the United States will get more than the average precipitation, while parts of the Midwest and the Great Lakes regions will get below-normal precipitation.

It appears that El Niño is partly responsible for the warmer temperatures on the West Coast. El Niño happens when the equatorial Pacific Ocean warms, which in turn sloshes warm water and humid air east toward the Americas. El Niño also tends to lead to the easternly extension of the jetstream from southeast of Japan to across the Pacific Basin, and to a low-pressure system in the northeast Pacific, Baxter said.

All of these factors tend to "lead to anomalous warm air convection in western United States and southern Alaska," Baxter said. (In another words, you have warm air where you normally wouldn't.) "And so you tend to have less cold air intrusions there. You also tend to have more storm activity across the southern tier of the U.S., and so that is that increased stormtrack there."

Climate change is also playing a role in this winter's weather, although it can be difficult to suss just how much, Baxter said. That's because so many factors influence the weather, such as increased greenhouse gas emissions and decadal changes in ocean patterns , and so it can be challenging to determine which signals are coming from where.

"Part of the challenge is just disentangling these things," Baxter said. "Climate now is higher than the fixed 30-year base period that we've used … and a good portion of that is long-term climate change."

Instead of taking the average of the past 30 years, climatologists are finding they can get a more accurate picture of the current climate by taking an average of just the past 15 years. And, according to NOAA and NASA, the five warmest years on record happened in the 2010s, while the 10 warmest years on record have occurred since 1998, Climate Central reported earlier this year.

Thanx Laura eggel . Senior Writer

Originally published on Live Science

Knight Sha

Credit: Shutterstock

Just over half of the United States has no need to fear an exceptionally frigid, frozen winter in the coming months — instead, they'll likely experience a warmer and wetter winter than usual, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center.

In the three coming months — December, January and February — the West Coast, the Mountain states and chunks of the Midwest and Northeast (although not New York or Boston) are all forecast to have above-normal temperatures for the season, as well as increased precipitation (meaning rain and snow), the Climate Prediction Center announced at a news conference yesterday (Nov. 15).

The warm and wet winter is due, in part, to weather patterns such as El Niño and decadal changes in ocean patterns , as well as climate change, said Stephen Baxter, a meteorologist and seasonal forecaster at the NOAA Climate Prediction Center. [Winter Wonderland: Images of Stunning Snowy Landscapes]

During the news conference, Baxter first presented the weather outlook for December, which is shown below. Areas that are red, orange and yellow are predicted to have above-normal winter temperatures, he said. The blue region covering the Great Lakes region is expected to be cooler than usual. Meanwhile, the white-colored areas in the United States are expected to have typical winter temperatures.

The December 2018 outlook for average temperature (left) and precipitation (right).Credit: NOAA

As for December precipitation (the map on the right), the green swaths over parts of California, the Mountain states and the Southeast indicate above-normal rainfall, while the yellow patches going diagonally from Texas to Maine show that those regions will likely receive less precipitation than average.

The December-January-February temperature outlook is slightly different. Notice how — in the map shown below — the above-average temperatures still cover Alaska and much of the American West and Midwest, but that the predicted cold spot over the Great Lakes area disappears.

The December, January and February average for temperature (left) and precipitation (right).Credit: NOAA

The three-month precipitation outlook shows a different story. It's predicted that the lower tier of the United States will get more than the average precipitation, while parts of the Midwest and the Great Lakes regions will get below-normal precipitation.

It appears that El Niño is partly responsible for the warmer temperatures on the West Coast. El Niño happens when the equatorial Pacific Ocean warms, which in turn sloshes warm water and humid air east toward the Americas. El Niño also tends to lead to the easternly extension of the jetstream from southeast of Japan to across the Pacific Basin, and to a low-pressure system in the northeast Pacific, Baxter said.

All of these factors tend to "lead to anomalous warm air convection in western United States and southern Alaska," Baxter said. (In another words, you have warm air where you normally wouldn't.) "And so you tend to have less cold air intrusions there. You also tend to have more storm activity across the southern tier of the U.S., and so that is that increased stormtrack there."

Climate change is also playing a role in this winter's weather, although it can be difficult to suss just how much, Baxter said. That's because so many factors influence the weather, such as increased greenhouse gas emissions and decadal changes in ocean patterns , and so it can be challenging to determine which signals are coming from where.

"Part of the challenge is just disentangling these things," Baxter said. "Climate now is higher than the fixed 30-year base period that we've used … and a good portion of that is long-term climate change."

Instead of taking the average of the past 30 years, climatologists are finding they can get a more accurate picture of the current climate by taking an average of just the past 15 years. And, according to NOAA and NASA, the five warmest years on record happened in the 2010s, while the 10 warmest years on record have occurred since 1998, Climate Central reported earlier this year.

Thanx Laura eggel . Senior Writer

Originally published on Live Science

Knight Sha

Friday, November 16, 2018

Tuesday, November 13, 2018

Glaciers Created a Huge 'Flour' Dust Storm in Greenland

By Rafi Letzter, Staff Writer | November 2, 2018

A large plume of "glacier flour" blew off of Greenland Sept. 29.Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

If you're in Greenland and a strange cloud darkens the sky, that cloud might be made up of something scientists call "glacier flour."

Researchers have written and speculated about glacier-flour dust storms in Greenland for a long time, according to NASA. But it took until this September for investigators to spot such a massive plume of the elusive dust forming and drifting 80 miles (130 kilometers) northwest of the far-northern village of Ittoqqortoormiit. Glacier flour is a fine dust created when glaciers pulverize rocks, NASA wrote. While satellites had occasionally spotted smaller storms of the stuff, this one was "by far the largest."

"We have seen a few examples of small dust events before this one, but they are quite difficult to spot with satellites because of cloud cover," Joanna Bullard, a professor of physical geography at Loughborough University in the United Kingdom, said in a NASA statement. "When dust events do happen, field data from Iceland and West Greenland indicate that they rarely last longer than two days." [7 Crazy Facts About Dust Storms]

The flour storm formed when a summer floodplain in the region dried out with late September's colder weather, leaving behind a large deposit of sediment carried south from more-northern glaciers.

NASA satellites watched the floodplain become grayer and grayer as it dried out, then saw the plume form when strong winds swept through the area on Sept. 29.

A composite image shows how the plume emerged over the course of several days.Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

According to NASA, storms like this are interesting because researchers just don't know much about them or how they affect the climate. While large dust storms found closer to the equator have known climate impacts, the role of glacial flour remains a mystery.

Originally published on Live Science.

Thanx Rafi letzter

Knight Jonny

A large plume of "glacier flour" blew off of Greenland Sept. 29.Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

If you're in Greenland and a strange cloud darkens the sky, that cloud might be made up of something scientists call "glacier flour."

Researchers have written and speculated about glacier-flour dust storms in Greenland for a long time, according to NASA. But it took until this September for investigators to spot such a massive plume of the elusive dust forming and drifting 80 miles (130 kilometers) northwest of the far-northern village of Ittoqqortoormiit. Glacier flour is a fine dust created when glaciers pulverize rocks, NASA wrote. While satellites had occasionally spotted smaller storms of the stuff, this one was "by far the largest."

"We have seen a few examples of small dust events before this one, but they are quite difficult to spot with satellites because of cloud cover," Joanna Bullard, a professor of physical geography at Loughborough University in the United Kingdom, said in a NASA statement. "When dust events do happen, field data from Iceland and West Greenland indicate that they rarely last longer than two days." [7 Crazy Facts About Dust Storms]

The flour storm formed when a summer floodplain in the region dried out with late September's colder weather, leaving behind a large deposit of sediment carried south from more-northern glaciers.

NASA satellites watched the floodplain become grayer and grayer as it dried out, then saw the plume form when strong winds swept through the area on Sept. 29.

A composite image shows how the plume emerged over the course of several days.Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

According to NASA, storms like this are interesting because researchers just don't know much about them or how they affect the climate. While large dust storms found closer to the equator have known climate impacts, the role of glacial flour remains a mystery.

Originally published on Live Science.

Thanx Rafi letzter

Knight Jonny

Monday, November 12, 2018

The Seafloor Is Dissolving Away. And Humans Are to Blame.

By Stephanie Pappas, Live Science Contributor | November 5, 2018

Carbon emissions are dissolving the seafloor, especially in the Northern Atlantic Ocean. Shown here, Azkorri beach in Basque Country in northern Spain.Credit: Inaki Bolumburu/Shutterstock

Climate change reaches all the way to the bottom of the sea.

The same greenhouse gas emissions that are causing the planet's climate to change are also causing the seafloor to dissolve. And new research has found the ocean bottom is melting away faster in some places than others.

The ocean is what's known as a carbon sink: It absorbs carbon from the atmosphere. And that carbon acidifies the water. In the deep ocean, where the pressure is high, this acidified seawater reacts with calcium carbonate that comes from dead shelled creatures. The reaction neutralizes the carbon, creating bicarbonate.

Over the millennia, this reaction has been a handy way to store carbon without throwing the ocean's chemistry wildly out of whack. But as humans have burned fossil fuels, more and more carbon has ended up in the ocean. In fact, according to NASA, about 48 percent of the excess carbon humans have pumped into the atmosphere has been locked away in the oceans.

-- 7 Ways the Earth Changes in the Blink of an Eye]

All that carbon means more acidic oceans, which means faster dissolution of calcium carbonate on the seafloor. To find out how quickly humanity is burning through the ocean floor's calcium carbonate supply, researchers led by Princeton University atmospheric and ocean scientist Robert Key estimated the likely dissolution rate around the world, using water current data, measurements of calcium carbonate in seafloor sediments and other key metrics like ocean salinity and temperature. They compared the rate with that before the industrial revolution.

Their results, published Oct. 29 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, were a mix of good and bad news. The good news was that most areas of the oceans didn't yet show a dramatic difference in the rate of calcium carbonate dissolution prior to and after the industrial revolution. However, there are multiple hotspots where human-made carbon emissions are making a big difference — and those regions may be the canaries in the coalmine.

The biggest hotspot was the western North Atlantic, where anthropogenic carbon is responsible for between 40 and 100 percent of dissolving calcium carbonate. There were other small hotspots, in the Indian Ocean and in the Southern Atlantic, where generous carbon deposits and fast bottom currents speed the rate of dissolution, the researchers wrote.

The western North Atlantic is where the ocean layer without calcium carbonate has risen 980 feet (300 meters). This depth, called the calcite compensation depth, occurs where the rain of calcium carbonate from dead animals is essentially canceled out by ocean acidity. Below this line, there is no accumulation of calcium carbonate.

The rise in depth indicates that now that there is more carbon in the ocean, dissolution reactions are happening more rapidly and at shallower depths. This line has moved up and down throughout millennia with natural variations in the Earth's atmospheric makeup. Scientists don't yet know what this alteration in the deep sea will mean for the creatures that live there, according to Earther, but future geologists will be able to see man-made climate change in the rocks eventually formed by today's seafloor. Some current researchers have already dubbed this era the Anthropocene, defining it as the point at which human activities began to dominate the environment.

"Chemical burndown of previously deposited carbonate-rich sediments has already begun and will intensify and spread over vast areas of the seafloor during the next decades and centuries, thus altering the geological record of the deep sea," Key and his colleagues wrote. "The deep-sea benthic [bottom] environment, which covers ~60 percent of our planet, has indeed entered the Anthropocene."

Originally published on Live Science.

Thanx Stephanie Pappas

Knight Sha

Carbon emissions are dissolving the seafloor, especially in the Northern Atlantic Ocean. Shown here, Azkorri beach in Basque Country in northern Spain.Credit: Inaki Bolumburu/Shutterstock

Climate change reaches all the way to the bottom of the sea.

The same greenhouse gas emissions that are causing the planet's climate to change are also causing the seafloor to dissolve. And new research has found the ocean bottom is melting away faster in some places than others.

The ocean is what's known as a carbon sink: It absorbs carbon from the atmosphere. And that carbon acidifies the water. In the deep ocean, where the pressure is high, this acidified seawater reacts with calcium carbonate that comes from dead shelled creatures. The reaction neutralizes the carbon, creating bicarbonate.

Over the millennia, this reaction has been a handy way to store carbon without throwing the ocean's chemistry wildly out of whack. But as humans have burned fossil fuels, more and more carbon has ended up in the ocean. In fact, according to NASA, about 48 percent of the excess carbon humans have pumped into the atmosphere has been locked away in the oceans.

-- 7 Ways the Earth Changes in the Blink of an Eye]

All that carbon means more acidic oceans, which means faster dissolution of calcium carbonate on the seafloor. To find out how quickly humanity is burning through the ocean floor's calcium carbonate supply, researchers led by Princeton University atmospheric and ocean scientist Robert Key estimated the likely dissolution rate around the world, using water current data, measurements of calcium carbonate in seafloor sediments and other key metrics like ocean salinity and temperature. They compared the rate with that before the industrial revolution.

Their results, published Oct. 29 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, were a mix of good and bad news. The good news was that most areas of the oceans didn't yet show a dramatic difference in the rate of calcium carbonate dissolution prior to and after the industrial revolution. However, there are multiple hotspots where human-made carbon emissions are making a big difference — and those regions may be the canaries in the coalmine.

The biggest hotspot was the western North Atlantic, where anthropogenic carbon is responsible for between 40 and 100 percent of dissolving calcium carbonate. There were other small hotspots, in the Indian Ocean and in the Southern Atlantic, where generous carbon deposits and fast bottom currents speed the rate of dissolution, the researchers wrote.

The western North Atlantic is where the ocean layer without calcium carbonate has risen 980 feet (300 meters). This depth, called the calcite compensation depth, occurs where the rain of calcium carbonate from dead animals is essentially canceled out by ocean acidity. Below this line, there is no accumulation of calcium carbonate.

The rise in depth indicates that now that there is more carbon in the ocean, dissolution reactions are happening more rapidly and at shallower depths. This line has moved up and down throughout millennia with natural variations in the Earth's atmospheric makeup. Scientists don't yet know what this alteration in the deep sea will mean for the creatures that live there, according to Earther, but future geologists will be able to see man-made climate change in the rocks eventually formed by today's seafloor. Some current researchers have already dubbed this era the Anthropocene, defining it as the point at which human activities began to dominate the environment.

"Chemical burndown of previously deposited carbonate-rich sediments has already begun and will intensify and spread over vast areas of the seafloor during the next decades and centuries, thus altering the geological record of the deep sea," Key and his colleagues wrote. "The deep-sea benthic [bottom] environment, which covers ~60 percent of our planet, has indeed entered the Anthropocene."

Originally published on Live Science.

Thanx Stephanie Pappas

Knight Sha

Saturday, November 10, 2018

Will This Winter Be Mild or Wild? Here's What We Can Expect

By Mindy Weisberger, Senior Writer | October 18, 2018

The winter outlook 2018-2019 map for temperature shows higher than average temperatures across much of the U.S.Credit: NOAA

Most of the United States can look forward to a mild winter with above-average temperatures, particularly in Alaska, Hawaii and the northern and western states, experts with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) announced today (Oct. 18).

Officials with NOAA's Climate Prediction Center (CPC) shared their predictions at a news conference, describing the outlook for winter precipitation and temperatures in the U.S. from December 2018 through February 2019.

Below-average temperatures are expected to be scarce in every part of the U.S., but there's likely to be plenty of snow or rain, with wetter-than-average conditions predicted for the southern part of the country and up into the mid-Atlantic states, according to the NOAA winter outlook. [In Photos: Best National Parks to Visit During Winter]

A developing El Niño — part of an ocean-climate cycle that can influence weather — could also leave its mark on the winter weather, as El Niño typically brings wetter conditions to the southern U.S., while shaping warm, dry conditions in the North, Mike Halpert, the CPC's deputy director, explained at the news conference.

Northern Florida and southern Georgia have the highest probability of experiencing a wetter-than-average winter, according to the report.

Though El Niño is still taking shape, there's a very good chance — about 70 to 75 percent — that it will emerge over the next few months and persist through the winter, Halpert said. El Niño is part of a climate cycle known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO); during El Niño, warm Pacific Ocean waters shift to the eastern coast of South America. In a strong El Niño year, ocean temperatures are even warmer than average. This phenomenon heats the air above the water and sets up a feedback loop between the sea and the atmosphere, which can dramatically impact weather patterns.

A powerful El Niño can bring unusually warm winter temperatures to the U.S. The winter of 2015 to 2016, which took place during the strongest El Niño in 60 years, was the warmest winter on record for the continental U.S., Halpert said.

However, this year's El Niño is anticipated to be much weaker than that, he added.

As for drought predictions, some relief is expected in Arizona, New Mexico, the southern parts of Colorado and Utah, and the coastal Pacific Northwest.

But drought conditions are expected to persist in the northern Plains states; in Southern California and the interior parts of the Pacific Northwest; and in the central Rockies, the central Plains states and the central Great Basin.

While there is always a certain amount of uncertainty in long-term weather and drought predictions such as these, the track record for the accuracy of the CPC seasonal outlooks is about 40 percent, up from a previous estimate of 30 percent, Halpert said.

"That's the general level for these type of forecasts," he added.

Originally publishedon Live Science.

Thanx Mindy Weisberger

Knight Man

The winter outlook 2018-2019 map for temperature shows higher than average temperatures across much of the U.S.Credit: NOAA

Most of the United States can look forward to a mild winter with above-average temperatures, particularly in Alaska, Hawaii and the northern and western states, experts with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) announced today (Oct. 18).

Officials with NOAA's Climate Prediction Center (CPC) shared their predictions at a news conference, describing the outlook for winter precipitation and temperatures in the U.S. from December 2018 through February 2019.

Below-average temperatures are expected to be scarce in every part of the U.S., but there's likely to be plenty of snow or rain, with wetter-than-average conditions predicted for the southern part of the country and up into the mid-Atlantic states, according to the NOAA winter outlook. [In Photos: Best National Parks to Visit During Winter]

A developing El Niño — part of an ocean-climate cycle that can influence weather — could also leave its mark on the winter weather, as El Niño typically brings wetter conditions to the southern U.S., while shaping warm, dry conditions in the North, Mike Halpert, the CPC's deputy director, explained at the news conference.

Northern Florida and southern Georgia have the highest probability of experiencing a wetter-than-average winter, according to the report.

Though El Niño is still taking shape, there's a very good chance — about 70 to 75 percent — that it will emerge over the next few months and persist through the winter, Halpert said. El Niño is part of a climate cycle known as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO); during El Niño, warm Pacific Ocean waters shift to the eastern coast of South America. In a strong El Niño year, ocean temperatures are even warmer than average. This phenomenon heats the air above the water and sets up a feedback loop between the sea and the atmosphere, which can dramatically impact weather patterns.

A powerful El Niño can bring unusually warm winter temperatures to the U.S. The winter of 2015 to 2016, which took place during the strongest El Niño in 60 years, was the warmest winter on record for the continental U.S., Halpert said.

However, this year's El Niño is anticipated to be much weaker than that, he added.

As for drought predictions, some relief is expected in Arizona, New Mexico, the southern parts of Colorado and Utah, and the coastal Pacific Northwest.

But drought conditions are expected to persist in the northern Plains states; in Southern California and the interior parts of the Pacific Northwest; and in the central Rockies, the central Plains states and the central Great Basin.

While there is always a certain amount of uncertainty in long-term weather and drought predictions such as these, the track record for the accuracy of the CPC seasonal outlooks is about 40 percent, up from a previous estimate of 30 percent, Halpert said.

"That's the general level for these type of forecasts," he added.

Originally publishedon Live Science.

Thanx Mindy Weisberger

Knight Man

Thursday, November 8, 2018

Voters rejected most ballot measures aimed at curbing climate change

From Arizona to Colorado, voters reject measures to ramp up renewables and limit drilling.

Measures to curb climate change foundered in many Western states, but environmental advocates did see victories in Florida and Nevada. (Luis Velarde /The Washington Post)

By Brady Dennis and In Arizona, voters said no to accelerating the shift to renewable energy. In Colorado, they said no to an effort to sharply limit drilling on nonfederal land. And a measure to make Washington the first state to tax carbon emissions appears to have fallen short.

The failure of environmental ballot measures in Arizona and Colorado — and the likely defeat of a proposal to impose fees on carbon emissions in Washington state — underscore the difficulty of tackling a global problem such as climate change at the state and local level, where huge sums of money poured in on both sides.

Even as a U.N.-backed panel of scientists recently warned that the world has barely a decade to radically cut its emissions of greenhouse gases that fuel global warming, the Trump administration has been busy expanding oil and gas drilling and rolling back Obama-era efforts to mitigate climate change. Environmental advocates and Democratic lawmakers have placed much hope in state and local governments to counter those policies.

But while Tuesday saw the election of numerous candidates dedicated to climate action, individual ballot measures aimed at the same goal largely foundered.

“What we learned from this election, in states like Colorado, Arizona, and Washington, is that voters reject policies that would make energy more expensive and less reliable,” said Thomas Pyle, president of the American Energy Alliance, an industry-backed free-market advocacy group.

Richard Newell, president of the nonpartisan think tank Resources for the Future, drew a different conclusion.

“The complexities and politics of the clean energy transition are best navigated through a legislative process, which has been the basis for virtually all significant state level climate and renewable energy policy,” Newell said in an email. “I would not take this as a repudiation of public desire to address climate change, including through carbon pricing or clean energy standards, but rather that the details and who is engaged in the policy formulation matter, a lot. That’s tough to do through a ballot initiative.”

Even in the solidly blue state of Washington, initial results looked grim for perhaps the most consequential climate-related ballot measure in the country this fall: a statewide initiative that would have imposed a first-in-the-nation fee on emissions of carbon dioxide, the most prevalent of the greenhouse gases that drive global warming. While voters in King County, home to Seattle, turned out heavily in favor of the measure, residents across the rest of the state largely opposed it.

One bright spot for environmental advocates came in Nevada, where voters appeared poised to pass a measure similar to the one Arizonans rejected. It would require utilities to generate 50 percent of their electricity from renewables by 2030. The proposal was leading handily with most votes tallied Wednesday. But before the measure could become law, it has to survive a second vote in 2020.

Since President Trump took office, a handful of states — notably California — have vowed to serve as a counterweight on energy and environmental policy to a president who frequently dismisses the government’s own findings that human activity is warming the globe. In September, California codified into law a commitment to produce 100 percent of its electricity from carbon-free courses by 2045.

But Tuesday’s ballot question results demonstrate the limits to which other states are willing to follow California’s lead — particularly when campaigners against the proposals emphasize the potential impact on pocketbooks.

Supporters and proponents poured an eye-popping amount of money, more than $54 million, into the fight over the future of energy in Arizona. Only two Senate races in the country — in Florida and Texas — saw more spending this year.

The influx of cash underscores how much both sides believed was at stake. The ballot initiative would have amended the Arizona constitution to require electric utilities to use renewable energy for 50 percent of its power generation by 2035. That might seem easily within reach in sunny Arizona. But the state now gets only about 6 percent of its energy from the sun.

The state’s biggest utility, Arizona Public Service, or APS, emerged as the most fervent opponent of the proposal, pouring more than $30 million into a political action committee called Arizonans for Affordable Electricity. In an aggressive ad campaign, the group argued that the measure would cost households an additional $1,000 a year.

“We’ve said throughout this campaign there is a better way to create a clean-energy future for Arizona that is also affordable and reliable,” APS chief executive Don Brandt said in a statement Tuesday evening.

Meanwhile, an alliance of dozens of organizations called Clean Energy for a Healthy Arizona argued that the shift toward cleaner energy will improve public health and create good jobs in the state. The group got a huge assist from California billionaire investor and political activist Tom Steyer, who donated the lion’s share of the nearly $23.6 million raised through the end of September.

Twenty-nine states and the District already have programs known as Renewable Portfolio Standards, or RPS, that require utilities to ensure a certain amount of the electricity they sell comes from renewable resources. But only a fraction of those have targets as ambitious as the ones proposed this year in Arizona and Nevada. For instance, New York and New Jersey also have targets of 50 percent renewable energy by 2030. Hawaii would require 100 percent of its energy to be from renewable sources by 2045.

During the 2018 campaign, however, 11 Democratic candidates for governor vowed to try to get all of their respective states’ electricity from “clean” energy sources by the middle of the century, according to surveys done by the state affiliates of the League of Conservation Voters. Several of those candidates, including Jared Polis in Colorado, won their races.

In Colorado, environmental advocates failed to pass a measure known as Proposition 112. The initiative would have required new wells to be at least 2,500 feet from occupied buildings and other “vulnerable areas” such as parks and irrigation canals — a distance several times that of existing regulations. It also allows local governments to require even larger setbacks.

As oil production has soared in Colorado in recent years and the population has grown, more and more residents are living near oil and gas facilities. Those who supported the ballot measure argued it was necessary to reduce potential health risks and the noise and other nuisances of living near drilling sites. Opponents countered that the proposal would virtually eliminate new oil and gas drilling on nonfederal land in the state — they have derided it as an “anti-fracking” push — and claimed it would cost jobs and deprive local governments of tax revenue.

The industry-backed group, Protect Colorado, raised roughly $38 million this year as it opposed the controversial measure, which it says would “wipe out thousands of jobs and devastate Colorado’s economy for years to come.” By contrast, the main group backing the proposal, known as Colorado Rising for Health and Safety, raised about $1 million.

“We appreciate Colorado voters who realized what a devastating impact this measure would have had on our state’s economy, school funding, public safety and other local services, ” Karen Crummy, spokeswoman for Protect Colorado, said in an email late Tuesday.

Separately, Chip Rimer, chairman of the board for the Colorado Oil and Gas Association, called Proposition 112 “an extreme proposal” that would have devastated the state’s economy. “Moving forward we will continue working together with all stakeholders to develop solutions that ensure we can continue to deliver the energy we need, the economy we want and the environment we value,” he said in a statement.

Coloradans also rejected a separate but related measure Tuesday that would have amended the Colorado constitution to allow property owners to seek compensation if government actions devalue their property. The proposal has been sharply criticized by dozens of city councils and panned by Gov. John Hickenlooper (D), who called it “a dangerous idea” in which “unscrupulous developers and speculators could make claims on local governments for literally anything they think has hurt the value of their land.”

Meanwhile, in Washington, the effort to put a price on carbon emissions appeared on the verge of defeat early Wednesday, with 56.3 percent of voters rejecting the measure and 43.7 percent supporting it with two-thirds of votes counted. An official at the Washington secretary of state’s office said the vote-by-mail system in the state means it could take several days for a final vote tally.

Known as Initiative 1631, the measure would have made Washington the first state in the nation to tax carbon dioxide — an approach many scientists, environmental advocates and policymakers argue will be essential on a broad scale to nudge the world away from its reliance on fossil fuels.

But that proposal, like other environmental initiatives across the country, faced a bitter fight, pitting Big Oil refiners against a collection of advocates that includes unions, Native American groups, business leaders such as Bill Gates and former New York mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, as well as the state’s Democratic governor, Jay Inslee.

It also has set a state spending record along the way for a state ballot initiative. The group pressing for the carbon fee, known as the Clean Air, Clean Energy coalition, has raised more than $15 million. Meanwhile, oil companies belonging to the Western States Petroleum Association pumped more than $31 million into opposing the measure.

The initial $15-a-ton fee would have kicked in beginning in 2020, then increased $2 per ton (plus inflation) each year until 2035, when it would either freeze or rise, depending on whether the state had met its targets to slash greenhouse gas emissions.

Climate campaigners did win at least one victory Tuesday in the Sunshine State. Florida voters, perhaps with the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill still fresh in mind, overwhelmingly decided to amend the state’s constitution to ban offshore oil and gas drilling in state waters.

But even then, it was unclear whether offshore drilling alone motivated 69 percent of voters to support the measure. It was paired, oddly, with a proposal to prohibit indoor vaping.

Crusader Jenny , Nanook & Mika

Measures to curb climate change foundered in many Western states, but environmental advocates did see victories in Florida and Nevada. (Luis Velarde /The Washington Post)

By Brady Dennis and In Arizona, voters said no to accelerating the shift to renewable energy. In Colorado, they said no to an effort to sharply limit drilling on nonfederal land. And a measure to make Washington the first state to tax carbon emissions appears to have fallen short.

The failure of environmental ballot measures in Arizona and Colorado — and the likely defeat of a proposal to impose fees on carbon emissions in Washington state — underscore the difficulty of tackling a global problem such as climate change at the state and local level, where huge sums of money poured in on both sides.

Even as a U.N.-backed panel of scientists recently warned that the world has barely a decade to radically cut its emissions of greenhouse gases that fuel global warming, the Trump administration has been busy expanding oil and gas drilling and rolling back Obama-era efforts to mitigate climate change. Environmental advocates and Democratic lawmakers have placed much hope in state and local governments to counter those policies.

But while Tuesday saw the election of numerous candidates dedicated to climate action, individual ballot measures aimed at the same goal largely foundered.

“What we learned from this election, in states like Colorado, Arizona, and Washington, is that voters reject policies that would make energy more expensive and less reliable,” said Thomas Pyle, president of the American Energy Alliance, an industry-backed free-market advocacy group.

Richard Newell, president of the nonpartisan think tank Resources for the Future, drew a different conclusion.

“The complexities and politics of the clean energy transition are best navigated through a legislative process, which has been the basis for virtually all significant state level climate and renewable energy policy,” Newell said in an email. “I would not take this as a repudiation of public desire to address climate change, including through carbon pricing or clean energy standards, but rather that the details and who is engaged in the policy formulation matter, a lot. That’s tough to do through a ballot initiative.”

Even in the solidly blue state of Washington, initial results looked grim for perhaps the most consequential climate-related ballot measure in the country this fall: a statewide initiative that would have imposed a first-in-the-nation fee on emissions of carbon dioxide, the most prevalent of the greenhouse gases that drive global warming. While voters in King County, home to Seattle, turned out heavily in favor of the measure, residents across the rest of the state largely opposed it.

One bright spot for environmental advocates came in Nevada, where voters appeared poised to pass a measure similar to the one Arizonans rejected. It would require utilities to generate 50 percent of their electricity from renewables by 2030. The proposal was leading handily with most votes tallied Wednesday. But before the measure could become law, it has to survive a second vote in 2020.

Since President Trump took office, a handful of states — notably California — have vowed to serve as a counterweight on energy and environmental policy to a president who frequently dismisses the government’s own findings that human activity is warming the globe. In September, California codified into law a commitment to produce 100 percent of its electricity from carbon-free courses by 2045.

But Tuesday’s ballot question results demonstrate the limits to which other states are willing to follow California’s lead — particularly when campaigners against the proposals emphasize the potential impact on pocketbooks.

Supporters and proponents poured an eye-popping amount of money, more than $54 million, into the fight over the future of energy in Arizona. Only two Senate races in the country — in Florida and Texas — saw more spending this year.

The influx of cash underscores how much both sides believed was at stake. The ballot initiative would have amended the Arizona constitution to require electric utilities to use renewable energy for 50 percent of its power generation by 2035. That might seem easily within reach in sunny Arizona. But the state now gets only about 6 percent of its energy from the sun.

The state’s biggest utility, Arizona Public Service, or APS, emerged as the most fervent opponent of the proposal, pouring more than $30 million into a political action committee called Arizonans for Affordable Electricity. In an aggressive ad campaign, the group argued that the measure would cost households an additional $1,000 a year.

“We’ve said throughout this campaign there is a better way to create a clean-energy future for Arizona that is also affordable and reliable,” APS chief executive Don Brandt said in a statement Tuesday evening.

Meanwhile, an alliance of dozens of organizations called Clean Energy for a Healthy Arizona argued that the shift toward cleaner energy will improve public health and create good jobs in the state. The group got a huge assist from California billionaire investor and political activist Tom Steyer, who donated the lion’s share of the nearly $23.6 million raised through the end of September.

Twenty-nine states and the District already have programs known as Renewable Portfolio Standards, or RPS, that require utilities to ensure a certain amount of the electricity they sell comes from renewable resources. But only a fraction of those have targets as ambitious as the ones proposed this year in Arizona and Nevada. For instance, New York and New Jersey also have targets of 50 percent renewable energy by 2030. Hawaii would require 100 percent of its energy to be from renewable sources by 2045.

During the 2018 campaign, however, 11 Democratic candidates for governor vowed to try to get all of their respective states’ electricity from “clean” energy sources by the middle of the century, according to surveys done by the state affiliates of the League of Conservation Voters. Several of those candidates, including Jared Polis in Colorado, won their races.

In Colorado, environmental advocates failed to pass a measure known as Proposition 112. The initiative would have required new wells to be at least 2,500 feet from occupied buildings and other “vulnerable areas” such as parks and irrigation canals — a distance several times that of existing regulations. It also allows local governments to require even larger setbacks.

As oil production has soared in Colorado in recent years and the population has grown, more and more residents are living near oil and gas facilities. Those who supported the ballot measure argued it was necessary to reduce potential health risks and the noise and other nuisances of living near drilling sites. Opponents countered that the proposal would virtually eliminate new oil and gas drilling on nonfederal land in the state — they have derided it as an “anti-fracking” push — and claimed it would cost jobs and deprive local governments of tax revenue.

The industry-backed group, Protect Colorado, raised roughly $38 million this year as it opposed the controversial measure, which it says would “wipe out thousands of jobs and devastate Colorado’s economy for years to come.” By contrast, the main group backing the proposal, known as Colorado Rising for Health and Safety, raised about $1 million.

“We appreciate Colorado voters who realized what a devastating impact this measure would have had on our state’s economy, school funding, public safety and other local services, ” Karen Crummy, spokeswoman for Protect Colorado, said in an email late Tuesday.

Separately, Chip Rimer, chairman of the board for the Colorado Oil and Gas Association, called Proposition 112 “an extreme proposal” that would have devastated the state’s economy. “Moving forward we will continue working together with all stakeholders to develop solutions that ensure we can continue to deliver the energy we need, the economy we want and the environment we value,” he said in a statement.

Coloradans also rejected a separate but related measure Tuesday that would have amended the Colorado constitution to allow property owners to seek compensation if government actions devalue their property. The proposal has been sharply criticized by dozens of city councils and panned by Gov. John Hickenlooper (D), who called it “a dangerous idea” in which “unscrupulous developers and speculators could make claims on local governments for literally anything they think has hurt the value of their land.”

Meanwhile, in Washington, the effort to put a price on carbon emissions appeared on the verge of defeat early Wednesday, with 56.3 percent of voters rejecting the measure and 43.7 percent supporting it with two-thirds of votes counted. An official at the Washington secretary of state’s office said the vote-by-mail system in the state means it could take several days for a final vote tally.

Known as Initiative 1631, the measure would have made Washington the first state in the nation to tax carbon dioxide — an approach many scientists, environmental advocates and policymakers argue will be essential on a broad scale to nudge the world away from its reliance on fossil fuels.

But that proposal, like other environmental initiatives across the country, faced a bitter fight, pitting Big Oil refiners against a collection of advocates that includes unions, Native American groups, business leaders such as Bill Gates and former New York mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, as well as the state’s Democratic governor, Jay Inslee.

It also has set a state spending record along the way for a state ballot initiative. The group pressing for the carbon fee, known as the Clean Air, Clean Energy coalition, has raised more than $15 million. Meanwhile, oil companies belonging to the Western States Petroleum Association pumped more than $31 million into opposing the measure.

The initial $15-a-ton fee would have kicked in beginning in 2020, then increased $2 per ton (plus inflation) each year until 2035, when it would either freeze or rise, depending on whether the state had met its targets to slash greenhouse gas emissions.

Climate campaigners did win at least one victory Tuesday in the Sunshine State. Florida voters, perhaps with the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill still fresh in mind, overwhelmingly decided to amend the state’s constitution to ban offshore oil and gas drilling in state waters.

But even then, it was unclear whether offshore drilling alone motivated 69 percent of voters to support the measure. It was paired, oddly, with a proposal to prohibit indoor vaping.

Crusader Jenny , Nanook & Mika

Saturday, November 3, 2018

Canadian Wildlife Federation

Wildlife on the planet earth has, at the latest, broad spectrum calculation, including aquatic life, been reduced by 60%.... that is sixty percent. Just contemplate that for a moment fellow humans. The principal causes are climate change, pollution, loss of habitat and food sources, hunting and poaching. We cannot save a lot of these species from total extinction. Their situations have become irreversible.

In Canada, we have lost 50% of our wildlife. Our fecund northern wilderness has always had an over-abundance of mammals, predators and prey, amphibians and reptiles. I remember as a child, the sky could grow black with enormous flocks of birds. We camped near the grazing grounds of great stags and moose. We watched, from a distance, the bears fishing for salmon in the rapids. We could hear the wolves, lynx and bobcats calling at night. We stayed far away from the hunting grounds of the mountain lions who can reach over two hundred pounds and the big bears who were grumpy fellows who could kill with a swipe of their massive paws. I remember hauling big pickerel and trout from the waters by the dozen, fishing with my dad and uncle. I guess we thought it would always be that way and we were careless and thoughtless, along with the rest of the world. Global warming is a major cause of wildlife loss in our most northern regions. Global warming causes our climate to change and is like a cancer on the planet....It grows and grows, unrestrained. And, until we come up with a comprehensive solution, all we can do is try and reduce our carbon footprint and find a substitute for fossil fuels. It's the greatest tragedy in human history.

We should not worry about immigrants seeking asylum or terrorists sneaking into our country. The biggest crisis we face does not carry a gun or seek to overthrow the government. But it will destroy the world nonetheless.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)